The Federal Reserve did a study that looked into the financial habits of Canadians whose neighbors won the lottery. The neighbors of people who struck it rich were more likely to increase their spending, take on more debt, put more money into speculative investments, and eventually file for bankruptcy. And the larger the winnings, the more likely that others in that neighborhood would go bankrupt.

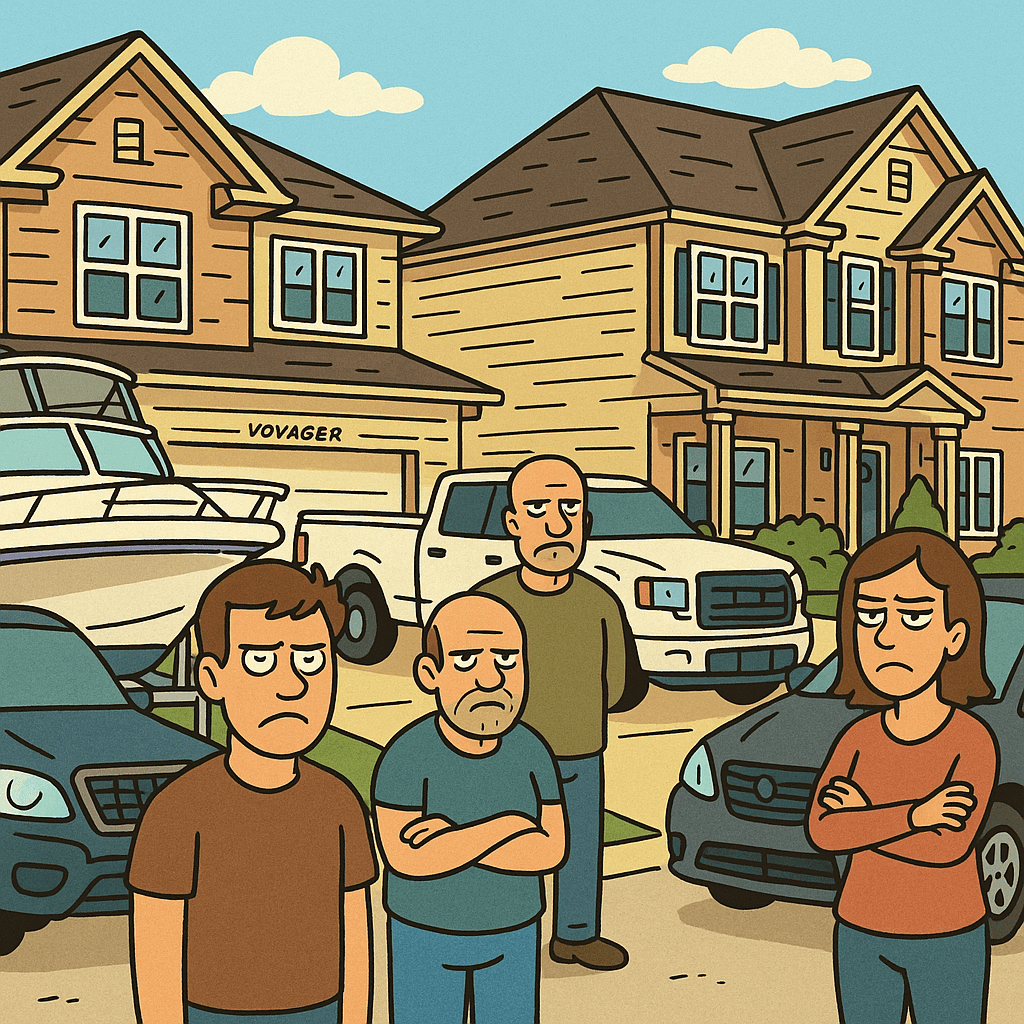

It’s in our flawed nature to compare ourselves to others, particularly people we see and interact with every day. Money insecurity leads us to compete and not appreciate what we have. Also true, though, is that the research shows one thing for certain: The Joneses aren’t very happy.

An examination of 259 different independent samples found that materialism was “associated with significantly lower well-being” and was a poor way of meeting psychological needs. The researchers’ findings suggest that this association holds across different demographics, participants, and cultural factors. Another meta-analysis of 92 studies found that those pursuing goals of growth, community, giving, and health experienced significantly higher levels of well-being than those pursuing the Jones-y goals of wealth, fame, or beauty.

You’ll never be content trying to keep up with the Joneses because there is an endless supply of them to keep up with. There are always people spending more money, taking nicer trips, buying bigger houses and making more money than you are.

There was another classic psychological study that compared lottery winners with people who were paralyzed in an accident. Surprisingly, the lottery winners weren’t significantly happier than the average person and actually reported less enjoyment from everyday experiences. The big win seemed to raise their expectations, which made small daily pleasures feel less satisfying.

In contrast, many accident victims rated themselves as moderately happy, despite their life-altering injuries. While thinking about their past lives sometimes made them feel worse, they still found deep meaning and enjoyment in ordinary things because they appreciated them more. After major life changes, people adjust their expectations. Lottery winners adjusted upward and felt less satisfied. Accident victims adjusted downward and found more value in the little things.

________________________

Many of the behaviors that have made humans such a successful species, also make it difficult to be good, long-term investors. Our overreaction to short-term, visible, in-the-moment risks, is just one of them. It was important for our ancestors to run first if they heard something in the bushes that could be hungry tiger. The investment issue that we are currently worrying about is very unlikely to be as vital as we believe it to be, but it is very human to act as if it is.

_________________________

Nothing was the same after June 28, 1914. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand triggered a chain of events that led to WWI and closed the NYSE for months. One month to the day of the assassination, Austria-Hungary declared war. Three days later, Henry Noble, president of the NYSE, closed the exchange. Other regional U.S. exchanges in Chicago, Baltimore, San Francisco, Philadelphia, and other cities followed suit. Most major exchanges around the world closed too.

Noble knew that wars demanded funds. Foreign investors could make a run on the exchange, selling securities to raise cash. The cash could then be converted into gold and shipped back to Europe. That put the U.S., being on the gold standard, in a tricky spot. Depleting the U.S. gold reserves would put faith in the dollar and adherence to the gold standard at risk.

- June 28, 1914 – Archduke Ferdinand assassinated. Dow closes the next day at 57.9.

- July 28, 1914 – Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia – World War 1 begins: Dow closed 55.3.

- July 30, 1914 – Dow closes 51.7.

- July 31, 1914 – NYSE & regional U.S. exchanges close the markets

- December 12, 1914 – NYSE reopens stock market with trading limitations.

- December 14, 1914 – Dow closes 56.8.

- December 14, 1915 – Dow closes 98.3.

When the stock market reopened December 12, 1914, investors had four and a half months to reassess the business environment in war time. And business was good. Over the next 12 months, the Dow soared 73% (Dec. 14, 1914, to Dec. 14, 1915, not including dividends). The U.S. became the main food and war supplier for the Allies war effort. Companies like U.S. Steel and DuPont saw profits explode 5x and 10x respectively, in a year. Dividend payments did the same. WWI is the perfect example of why geopolitical events are hard to predict. The market reacts in unexpected ways during scary confusing times.

______________________________

Reciprocity is a deeply human thing, and it applies directly to the nature of interest. If you show someone that you’re interested in them, they will reciprocate that curiosity by revealing what makes them so interesting. Believing that someone is boring is a failure of recognizing jthat fact. Boredom is almost always the result of a lack of curiosity, or the inability to see anything or anyone through the lens of a question. In a way, boredom is arrogance. It’s the acceptance of the belief that nothing is worth your interest because you already know what you need to about yourself, others, and the world. A curious mind is a humble one, as a prerequisite for curiosity is the acceptance that there is more to life than what you think you already know.

____________________________

We are a story-driven species. From cave walls to balance sheets, we look for narratives that explain the world and our place in it. And nowhere is this tendency more dangerous than when we only learn from the winners. When we allow survival alone to imply superiority. When the fact that someone or something made it through becomes enough proof that they knew what they were doing.

This is the essence of survivorship bias, and in the world of investing, it distorts almost everything. Consider the stock market, which is full of visible winners. We often hear stories of stocks that went 20x, fund managers who outperformed for a decade, companies that pivoted into success, and investors who became celebrities.

What about the others? The ones who didn’t make it? They’re barely mentioned, rarely studied, and almost never remembered. And so, the narrative we inherit is hopelessly incomplete.

Then there’s the most seductive arena of all: success stories. Business books, biographies, and podcast interviews are all proudly built on the same question: “How did you do it?”But that question, when asked only of survivors, creates a dangerous narrative. It turns randomness into wisdom and luck into method.

A founder who succeeded against all odds is praised for her vision, her grit, and her intuition. But what about the 100 others who had the same qualities and failed? What about the timing, the macro conditions, the investor interest, the random tailwinds that no one could have planned? None of that gets included in the final story. And so we start to think: this is how success works. This is the roadmap. Just do what she did.

Survivorship bias also affects how we view risk. When risky behaviour pays off, it’s reframed as boldness or foresight. But when it doesn’t, there’s no reframing…just silence. The lesson that reaches the public, though, is clear: take bold bets. It worked for him, it could work for you. But that’s the equivalent of watching five Russian roulette winners and deciding the game must be safe.

_________________________

Foreigners have steadily increased their holdings of US equities and currently own 18% of the US stock market, see chart below. This is the mirror image of a trade deficit. Foreigners selling goods to the US receive dollars in return, which are then used to purchase US assets, including US equities. If the trade deficit is eliminated, there will be fewer dollars for foreigners to recycle into the S&P 500.