There is an anxious, stomach-clenching feeling that the world is changing very fast, and that you’ll need to struggle very hard to keep up. The furious scramble to a place of psychological safety, to avoid being condemned to disaster and cast into the void………….

You don’t, actually, have to live like that. It won’t make you happier. It probably won’t even aid your career.

It’s worth briefly noting that of course there’s a mundane sense in which keeping up with changing times is a good idea. If you work in a job you’d like to retain, it’s wise to keep your skills fresh. If you see ways that a software tool might genuinely enhance what you do, you’d be foolish to refuse on principle to experiment with it. But that’s not the existential desperation I’m talking about here – that feeling of needing to claw your way to safety, so as not to tumble backwards into the abyss. Instead, you’re just making the sober judgment that, because a certain outcome matters to you, it makes sense to do certain things to try to obtain it.

The stomach-clench of anxiety isn’t anything like that. Rather, it emerges from the feeling that reality poses a fundamental threat to your security, so that hypervigilance and constant effort will be required to forestall annihilation. It implies that it’ll be very difficult indeed to make it to safety (with the corollary that if you fail, it’ll be because you didn’t try hard enough).

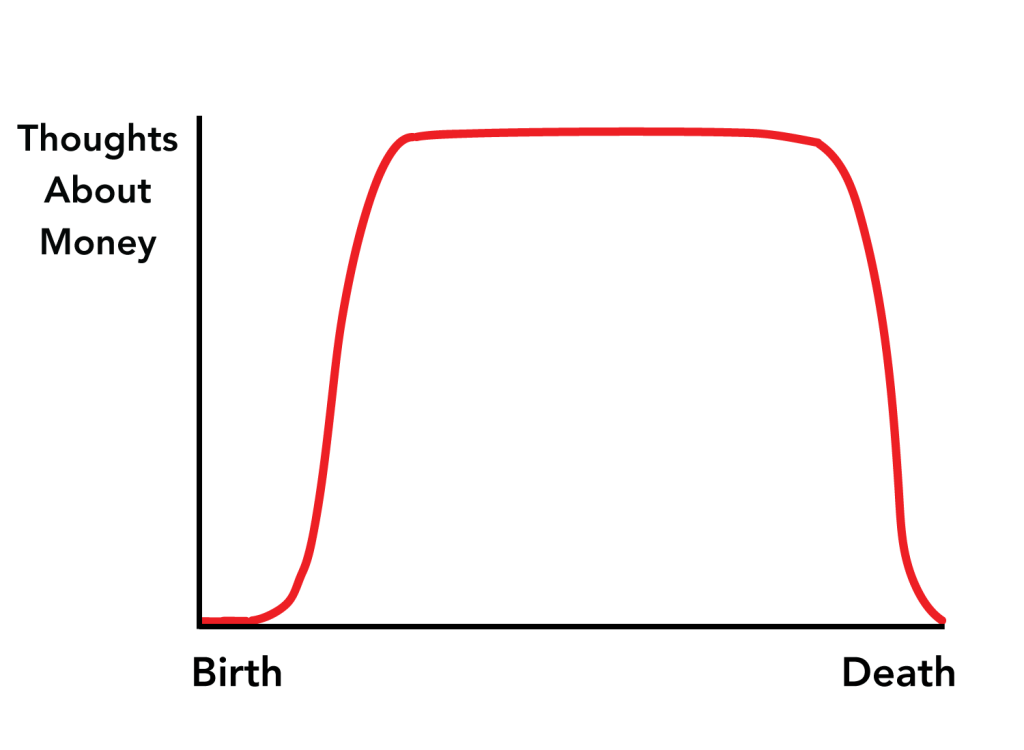

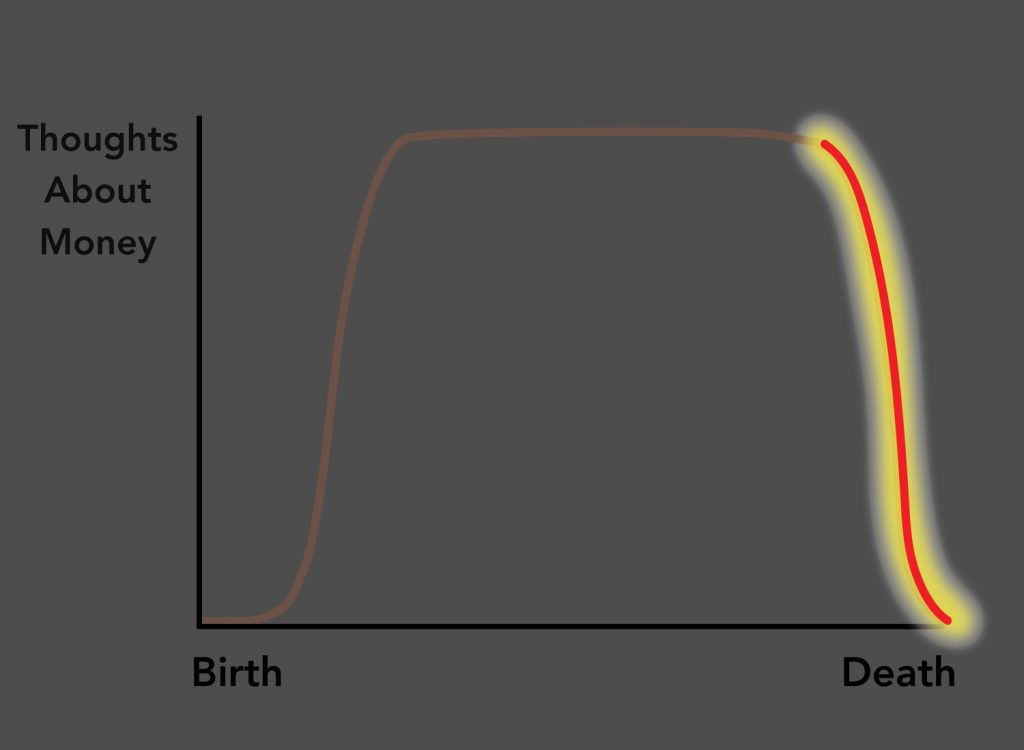

But this is one of those cases where the agony arises, in a sense, not from getting things out of proportion, but from not taking them far enough. Because for finite humans, it’s not “very difficult” to reach a place of safety from the onrush of events. It’s impossible. The moment of invulnerability never arrives. Even if you were to find a way to feel like a winner, technology-wise, by 2027, there’d be 2028 to worry about. Even if you felt completely secure in your career, there’d be your health, and the health of those you love, to worry about. And even if you and your family were the healthiest people alive, you might get hit by a bus tomorrow. Uncertainty is our basic state of existence, not something to be got through to the certainty beyond.

The reason “you’re not ready for what’s coming next”, in other words, is that we’re never ready for what’s coming next.

I’m not suggesting that when you grasp this insight you’ll immediately cease worrying about the future and be free of anxiety forever. (That hasn’t been my experience.) But it can free you up sufficiently to notice a different way of approaching life: not by anxiously bracing against impending doom, but by taking a deep breath and settling down a bit into the basic uncertainty of it all. And then, in that tremulous and vulnerable state, to navigate from one day to the next by choosing, from the paths available to you, whatever seems to lead in the direction of more aliveness.

There’s no reason this can’t involve immersing yourself in all manner of digital tools. But you’ll be relegating them to their proper role as tools, useful in some contexts and too limited to be useful in others, as opposed to gods you must appease, regardless of the cost to your experience of life.

___________________________

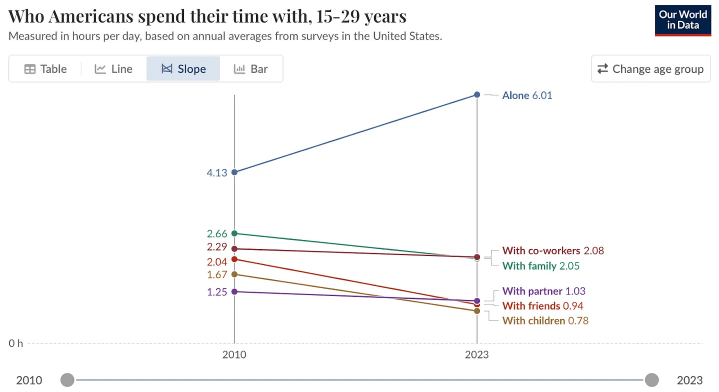

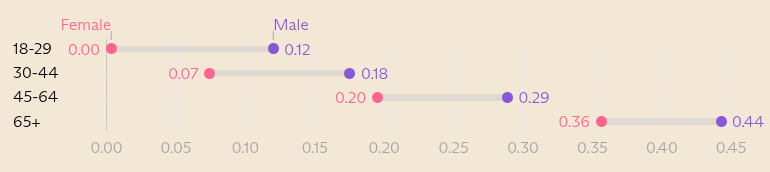

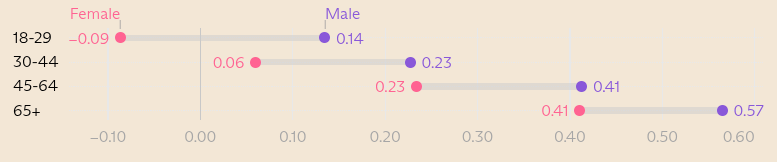

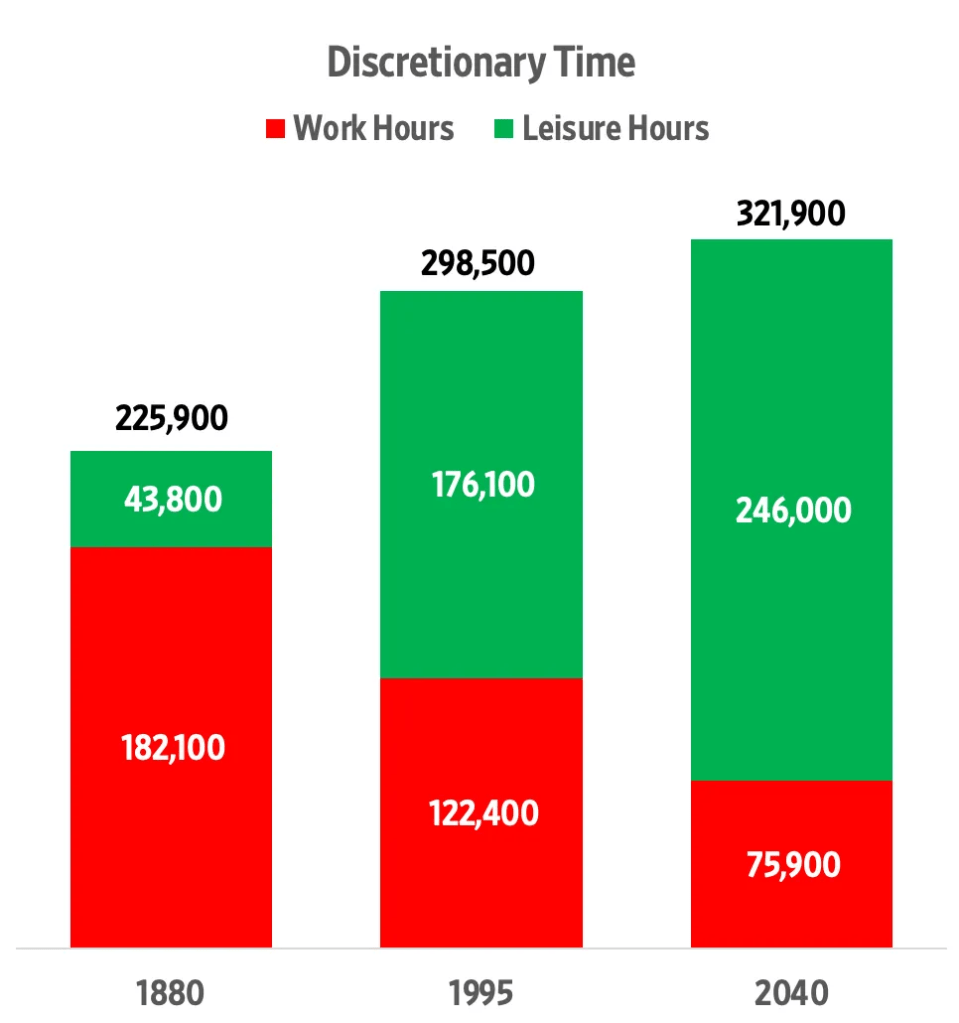

“Discretionary Hours” refers to time beyond sleep, meals, and hygiene. They are available for work, leisure, and other activities. “Work Hours” includes paid work, travel time to and from work, and household chores. The balance between work and leisure has shifted over time, particularly in the 20th century, due to factors like technological advancements and increased productivity

____________________________

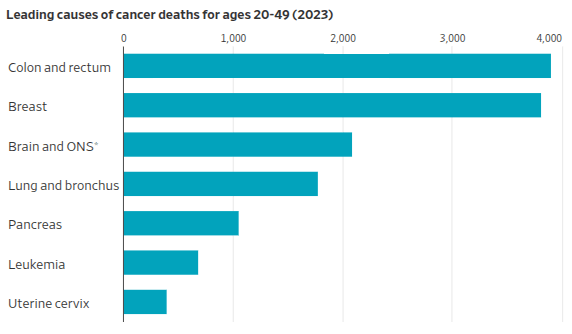

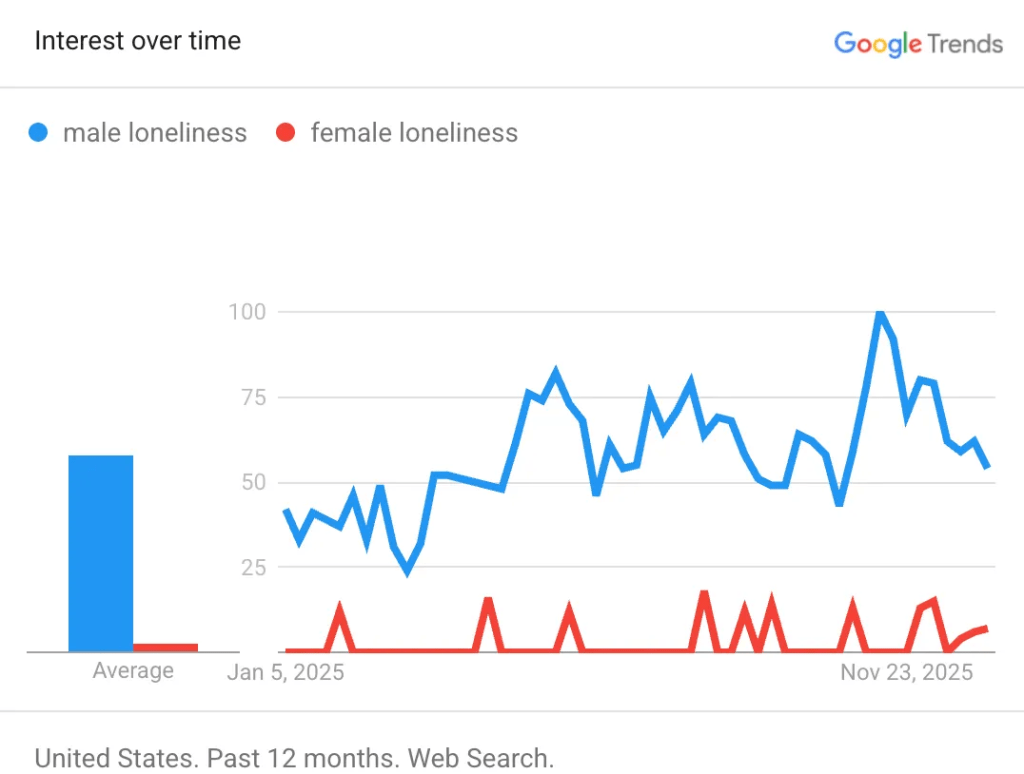

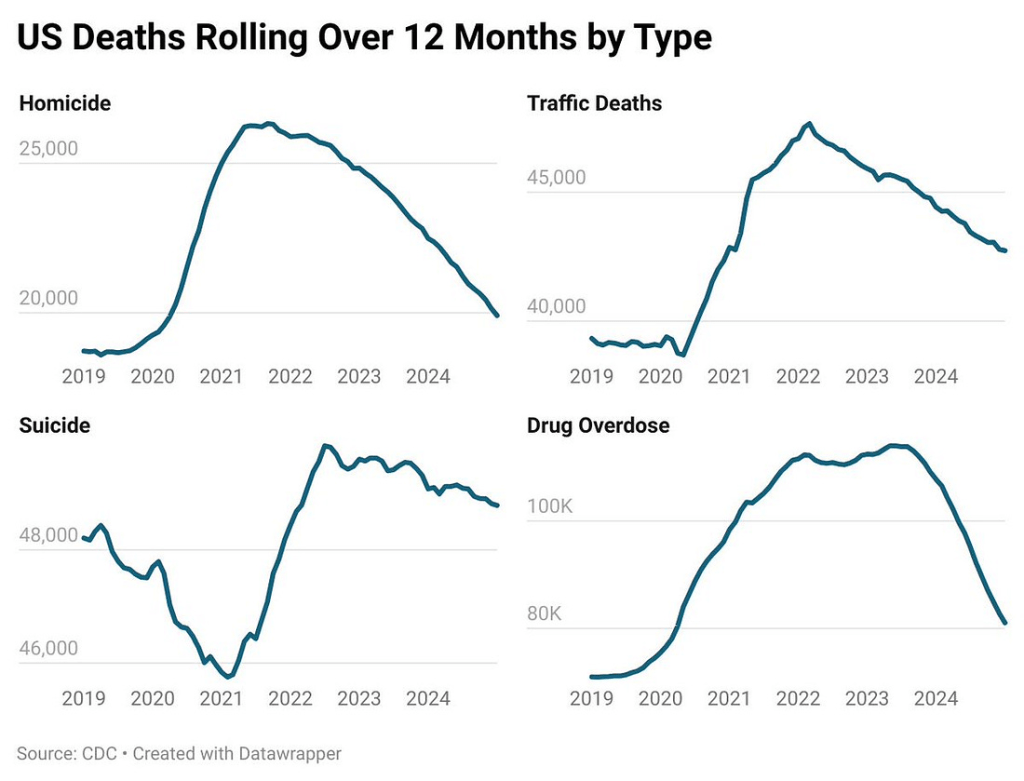

A bit of positive news. In the past 12 months, we’ve seen:

- the largest decline in US murder rate ever recorded

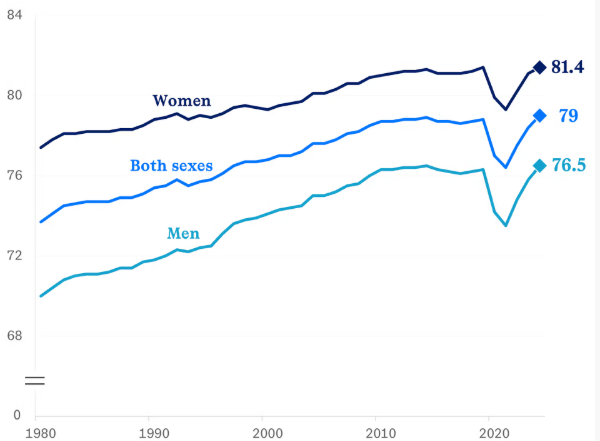

- huge declines in traffic fatalities and drug overdoses

- a surprising (and largely unreported) decline in teen anxiety and despair, coinciding with ongoing declines in suicide

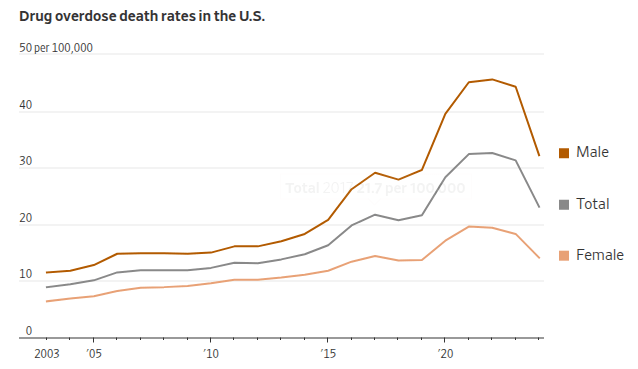

- continued advances in GLP-1 medicines that seem to reduce obesity, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and other illnesses that are currently under study

__________________________

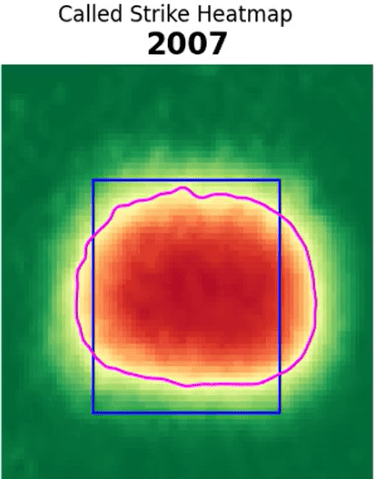

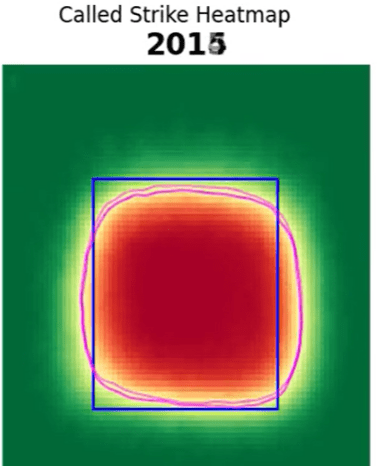

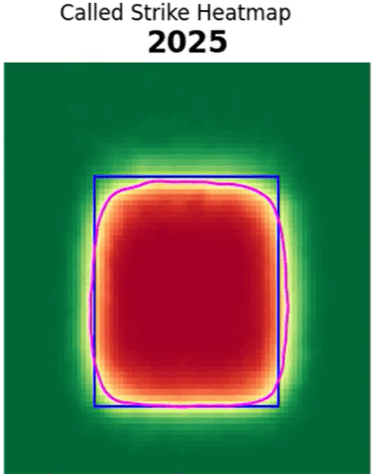

Baseball umpires have improved dramatically. The heat maps below show the evolution of the MLB strike zone from 2007 to 2025. The zone has changed dramatically, going from vibes to nearly matching the rule book definition perfectly.

________________________________

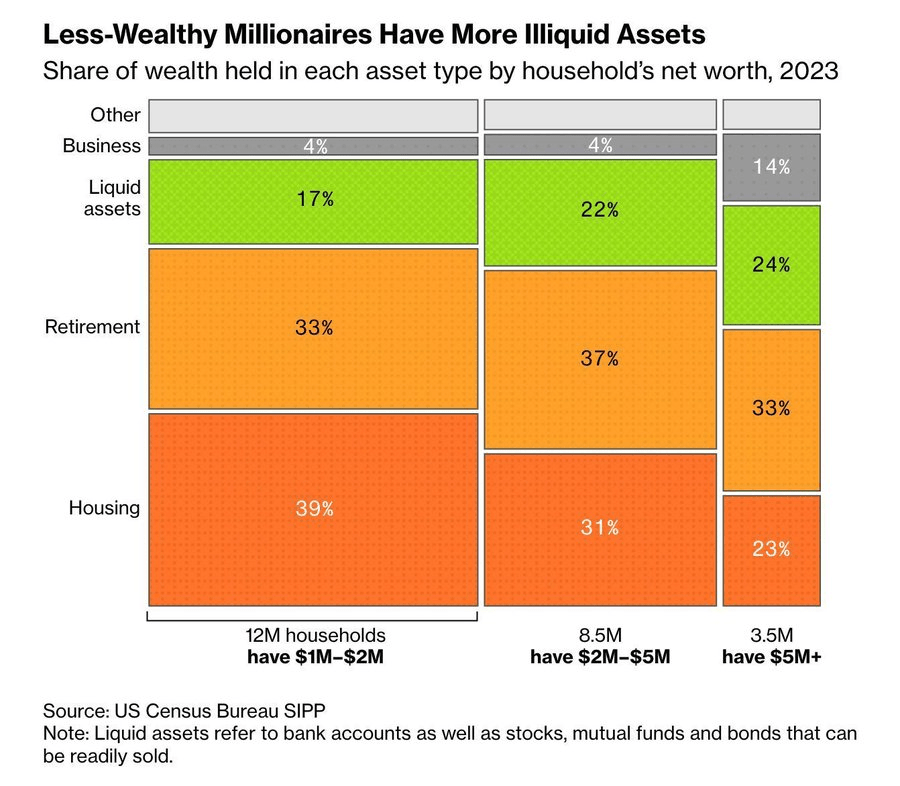

The truth about millionaires in America:

-Half have less than $2 million in net worth (and less than $340,000 in liquid assets)

-Most are NOT business owners

-Almost all are house/401k rich but cash poor

________________________________

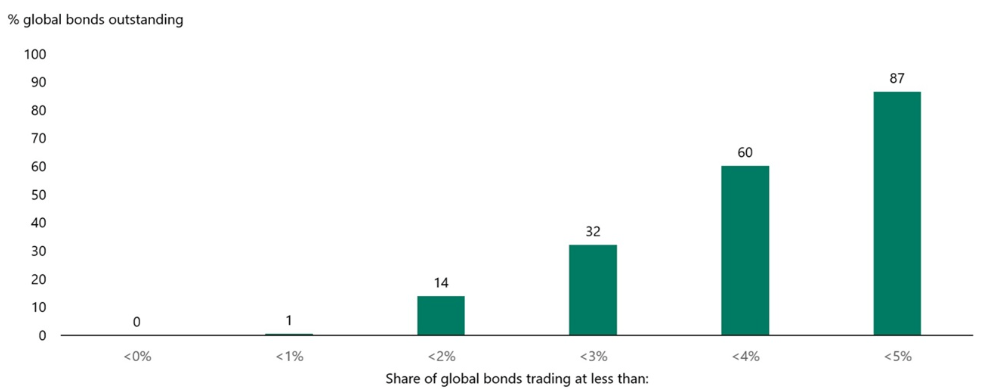

About 90% of all outstanding bonds in the world yield lower than 5%:

________________________________

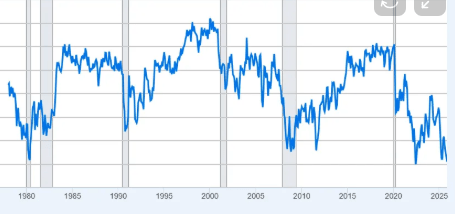

The falling number of public companies/stocks available to buy is a global phenomenon:

________________________________

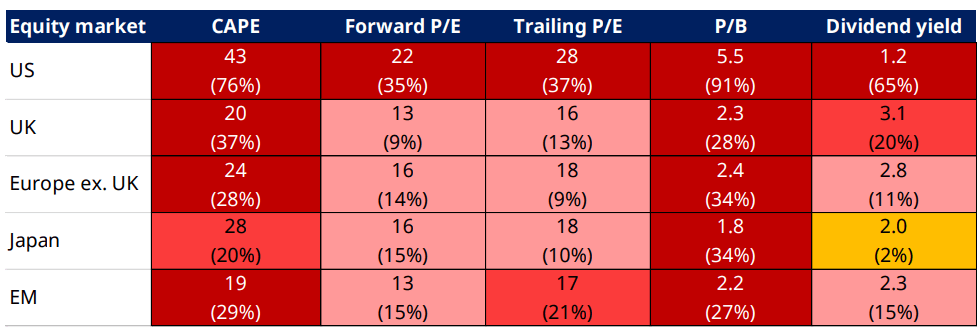

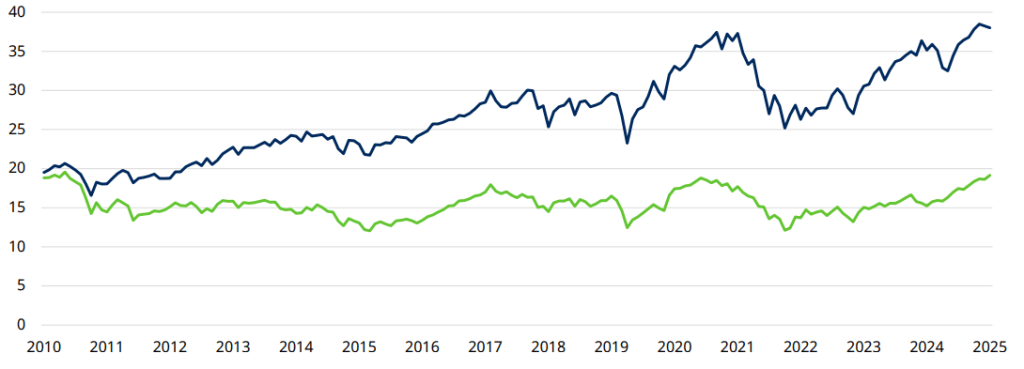

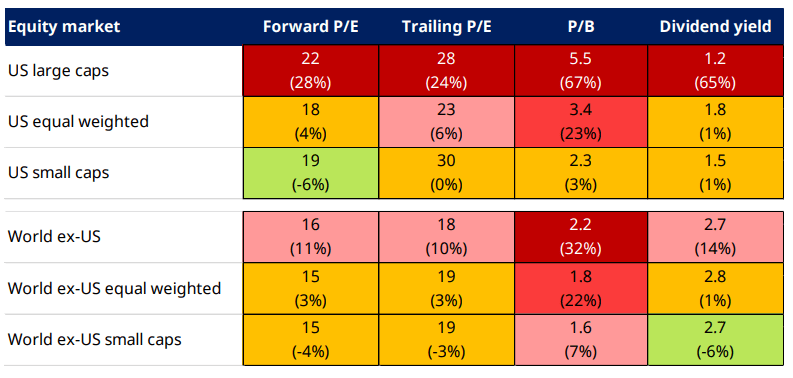

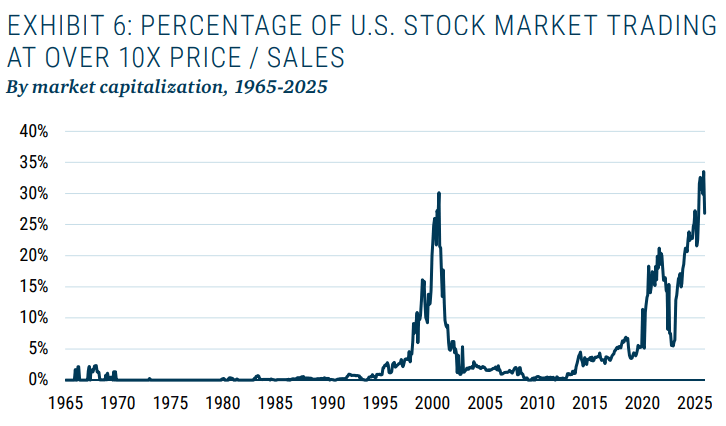

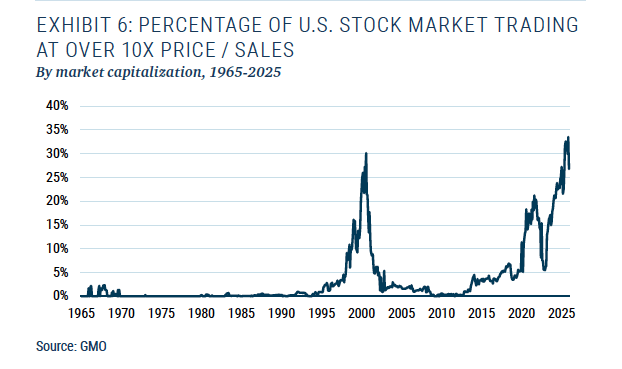

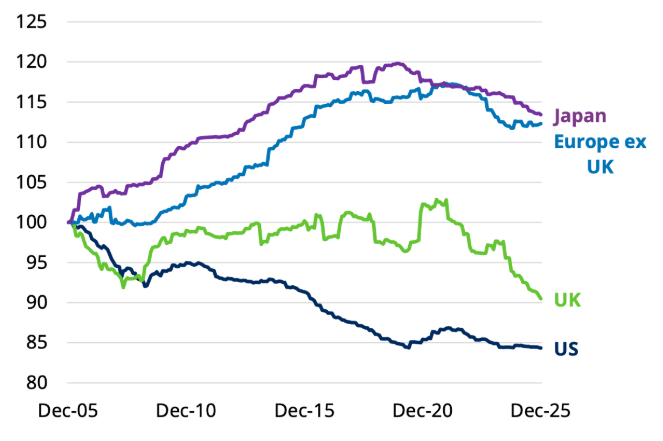

After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the P/E ratio for US stocks was similar to that of the rest of the world, but the surge in tech valuations has now pushed the US P/E ratio 40% higher:

_______________________________

What software companies are in more danger vs. more safe from the relentless A.I. disruption:

🔴 High danger — “Search layer” companies: Companies whose main value is making publicly available data easier to search through a fancy interface. This includes financial data terminals built on licensed exchange data, legal research platforms built on public court records, and patent search tools. Many have already lost 40–60% of their value.

🟡 Medium danger — “Mixed portfolio” companies: Companies that have some proprietary assets but also rely on repackaging public information. The key question is: what percentage of their revenue comes from things AI can’t replace? (Think S&P Global — their credit ratings are safe, but their data analytics tools are exposed.)

🟢 Safer companies have one or more of these shields:

- They own data nobody else can get — Bloomberg’s real-time trading desk data, S&P’s credit ratings, Dun & Bradstreet’s business credit files. AI actually makes this more valuable since every AI agent needs it.

- They’re protected by regulations — Epic (hospital software) is shielded by HIPAA rules and FDA certifications. AI doesn’t change those requirements.

- They’re embedded in money flows — If your software processes payments or settles trades (like Stripe), AI sits on top of you, not instead of you.

- They have network effects — Bloomberg’s chat system works because everyone on Wall Street is on it. AI doesn’t change that.