In the 2008 best seller Nudge, the legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein and the economist Richard H. Thaler marshaled behavioral-science research to show how small tweaks could help us make better choices. An updated version of the book includes a section on what they called “sludge”—tortuous administrative demands, endless wait times, and excessive procedural fuss that impede us in our lives.

Sludge is often intentional,” said a professional that works in the customer service call center industry. “Of course. The goal is to put as much friction between you and whatever the expensive thing is. So the frontline person is given as limited information and authority as possible. And it’s punitive if they connect you to someone who could actually help.”

Helpfulness aside, I mentioned that I frequently felt like I was talking with someone alarmingly indifferent to my plight.

“That’s called good training,” Tenumah said. “What you’re hearing is a human successfully smoothed into a corporate algorithm, conditioned to prioritize policy over people. If you leave humans in their natural state, they start to care about people and listen to nuance, and are less likely to follow the policy.”

For some people, that humanity gets trained out of them. For others, the threat of punishment suppresses it. To keep bosses happy, Tenumah explained, agents develop tricks. If your average handle time is creeping up, hanging up on someone can bring it back down. If you’ve escalated too many times that day, you might “accidentally” transfer a caller back into the queue. Choices higher up the chain also add helpful friction, Tenumah said: Not hiring enough agents leads to longer wait times, which in turn weeds out a percentage of callers. Choosing cheaper telecom carriers leads to poor connection with offshore contact centers; many of the calls disconnect on their own.

“No one says, ‘Let’s do bad service,’” Tenumah told me. “Instead they talk about things like credit percentages”—the number of refunds, rebates, or payouts extended to customers. “My boss would say, ‘We spent a million dollars in credits last month. That needs to come down to 750.’ That number becomes an edict, makes its way down to the agents answering the phones. You just start thinking about what levers you have.”

“Does anyone tell them to pull those levers?” I asked.

“The brilliance of the system is that they don’t have to say it out loud,” Tenumah said. “It’s built into the incentive structure.”

That structure, he said, can be traced to a shift in how companies operate. There was a time when the happiness of existing customers was a sacred metric. CEOs saw the long arc of loyalty as essential to a company’s success. That arc has snapped. Everyone still claims to value customer service, but as the average CEO tenure has shortened, executives have become more focused on delivering quick returns to shareholders and investors. This means prioritizing growth over the satisfaction of customers already on board.

Customers are part of the problem too, Tenumah added. “We’ve gotten collectively worse at punishing companies we do business with,” he said. He pointed to a deeply unpopular airline whose most dissatisfied customers return only slightly less often than their most satisfied customers. “We as customers have gotten lazy. I joke that all the people who hate shopping at Walmart are usually complaining from inside Walmart.”

In other words, he said, companies feel emboldened to treat us however they want. “It’s like an abusive relationship. All it takes is a 20 percent–off coupon and you’ll come back.” Supervisors don’t tell customer service workers to deceive or thwart customers. But having them get frustrated and give up is the best way to meet numbers.

Sometimes they intentionally drop a call or feign technical trouble: “‘I’m sorry, the call … I can’t … I’m having a hard time hearing y—.’ It’s sad. Sometimes they drag out the call enough that customers get agitated, or say things that get them agitated, and they hang up.”

Even if an agent wanted to treat callers more humanely, much of the friction was structural, a longtime contact-center worker named Amayea Maat told me. For one, the different corners of a business were seldom connected, which forced callers to re-explain their problem over and over: more incentive to give up.

“And often they make the IVR”—interactive voice response, the automated phone systems we curse at—“really difficult to get through, so you get frustrated and go online.” Employees described working with one government agency that programmed its IVR to simply hang up on people who’d been on hold for a certain amount of time.

________________________

On June 12th, an anonymous trader opened a new account on Polymarket, an anonymous internet betting site that uses cryptocurrency to obscure the source of money. The new trader was interested in betting on one topic: whether the Israeli military would strike Iran within the next 24 hours, by Friday, June 13th.

As the 13th approached, most people thought it was unlikely, but this new account seemed convinced that airstrikes were imminent. The trades started during a one-hour period around 12pm; $1,728 of bets in the first one, then another $311, $280, $560. Then, between 10pm and midnight, with time running out, they accelerated their betting, showing their confidence by ramping up the bets, putting about $20,000 in total at risk.

Three and a half hours later, Israel struck Iran in a surprise attack—and the Polymarket trader cashed out. They had made a total of $134,000 in profits. After taking their winnings, they closed the account, never trading again. This was probably a case of geopolitical insider trading. Someone who knew that the strike was imminent decided to use that knowledge to make a lot of money anonymously through online betting markets.

This is pretty dystopian: individuals, state actors, even terrorist groups can decide to bet on their own behavior, even their own uses of violence. There’s nothing stopping someone who’s a high-profile political actor—or the people around them—from betting on an outcome, then making comments or posting something on, say, Truth Social or X, that inevitably affects public perceptions about a likely course of action. They can drive the price up or down at will, knowing full well that they can ultimately decide whether the value of a “share” goes to $0.00 or to $1.00. And then, they can anonymously cash out, with nobody the wiser. It’s the Wild West of insider trading.

____________________________

Nearly half of U.S. grandchildren (47%) live within 10 miles of a grandparent. Of those, significant numbers live even closer: 21% live between 1 and 5 miles, and 13% live within a walkable distance of 1 mile.

______________________________

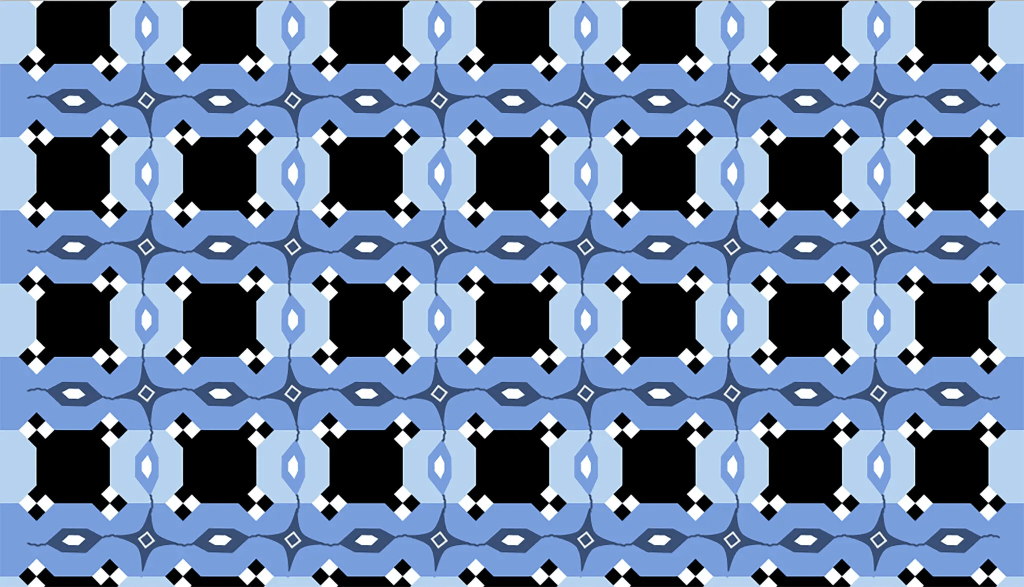

The blue horizontal bars in the picture below are parallel to each other:

_______________________________

Ranked: The World’s Most Common Passwords. The data comes from NordPass, which analyzed the most frequently used passwords based on a 2.5 terabyte database of credentials exposed by data breaches. All of the passwords below would take a hacker less than 1 second to crack.

According to NordPass, your password should be at least 20 characters long and include uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special symbols. They suggest that you never reuse passwords. If one account were to be compromised, other accounts that share the same password could also be at risk.

_______________________________

American household leverage is the lowest in 50 years. The leverage ratio is liabilities (mortgage, auto, credit, student loans) divided by the price of assets they own (stocks, bonds, real estate,).

Stock price gains help the top 10% wealthiest families disproportionately, but the biggest improvement in the leverage ratio above for most American families comes from home prices: