Everyone knows it’s hard to get college students to do the reading—remember books? But the attention-span crisis is not limited to the written word. Professors are now finding that they can’t even get film students—film students—to sit through movies.

I heard similar observations from 20 film-studies professors around the country. They told me that over the past decade, and particularly since the pandemic, students have struggled to pay attention to feature-length films.

A professor at the University of Southern California, home to perhaps the top film program in the country, said that his students remind him of nicotine addicts going through withdrawal during screenings: The longer they go without checking their phone, the more they fidget. Eventually, they give in.

He recently screened the 1974 Francis Ford Coppola classic The Conversation. At the outset, he told students that even if they ignored parts of the film, they needed to watch the famously essential and prophetic final scene. Even that request proved too much for some of the class. When the scene played, the professor noticed several students were staring at their phones.

Professors at Universities can track whether students watched films on the campus internal streaming platform. Fewer than 50 percent would even start the movies, he said, and only about 20 percent made it to the end. (Recall that these are students who chose to take a film class.)

After watching movies distractedly, if they watch them at all, students unsurprisingly can’t answer basic questions about what they saw. When a film professor at UW Madison asks what happens at the end of a film, more than half of the class picks one of the wrong options.

The professors I spoke with didn’t blame students for their shortcomings; they focused instead on how media diets have changed. From 1997 to 2014, screen time for children under age 2 doubled. And the screen in question, once a television, is now more likely to be a tablet or a smartphone. Students arriving in college today have no memory of a world before the infinite scroll. As teenagers, they spent nearly five hours a day on social media, with much of that time used for flicking from one short-form video to the next. An analysis of people’s attention while working on a computer found that they now switch between tabs or apps every 47 seconds.

A film and media-studies professor at Johns Hopkins, usually begins his course with an icebreaker: “What’s a movie you watched recently?” In the past few years, some students have struggled to name any film. A performing- and media-arts professor at Cornell University, has noticed a similar trend. Some of her students arrive having seen only Disney movies.

Of course, young people haven’t given up on movies altogether. But the feature films that they do watch now tend to be engineered to cater to their attentional deficit. In a recent appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience, Matt Damon, the star of many movies that college students may not have seen, said that Netflix has started encouraging filmmakers to put action sequences in the first five minutes of a film to get viewers hooked. And just because young people are streaming movies, it doesn’t mean they’re paying attention. When they sit down to watch, many are browsing social media on a second screen. Netflix has accordingly advised directors to have characters repeat the plot three or four times so that multitasking audiences can keep up with what’s happening.

___________________________

___________________________

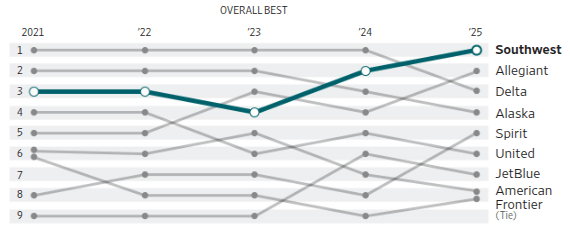

We rank nine major U.S. airlines on seven equally weighted operations metrics:

- on-time arrivals

- flight cancellations

- delays of 45 minutes or more

- baggage handling

- tarmac delays

- involuntary bumping

- passenger submissions (which are mostly complaints)

____________________________

To keep people splurging in mobile games on your phone like the Custom Street Racing, FarmVille and Words With Friends franchises, their publisher, Zynga, uses a secretive V.I.P. program that treats players like royalty. It is a tactic borrowed from casinos, which may offer a free meal or show tickets when they notice a player is losing more than usual on a slot machine.

Retaining big spenders is essential in the competitive world of mobile gaming, where roughly 90 percent of revenue can come from less than 5 percent of the player base.

The typical V.I.P. gamer is a retired or semiretired professional drawn in by the chance to meet new people online. The continuous stream of updates and seasonal features in mobile games can also create a feeling of purpose and productivity. They can choose to spend their surplus income on golf memberships or they can play FarmVille with their newfound friends in Australia for the weekend.

Players who pour hundreds or thousands of dollars into a game are known as whales, a term borrowed from the gambling world that many people in the industry avoid.

Preventing burnout was a key goal when casinos introduced V.I.P. programs. Harrah’s influential program, which began in 1997, used a digital tracking tool to detect when someone was losing more often than a slot machine’s predetermined odds. To stop players from forming a negative memory that might dissuade them from coming back, an alert would instruct a casino floor attendant to approach them with a reward.

____________________________

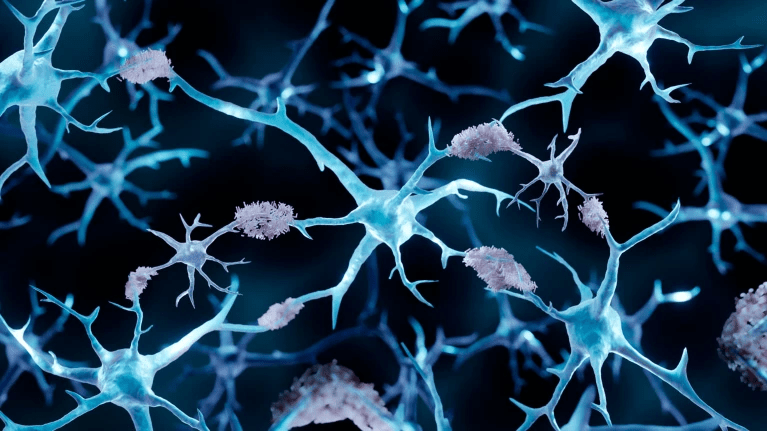

For decades, researchers have noted that cancer and Alzheimer’s disease are rarely found in the same person, fuelling speculation that one condition might offer some degree of protection from the other.

Now, a study in mice provides a possible molecular solution to the medical mystery: a protein produced by cancer cells seems to infiltrate the brain, where it helps to break apart clumps of misfolded proteins that are often associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The study was 15 years in the making and could help researchers to design drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

____________________________________

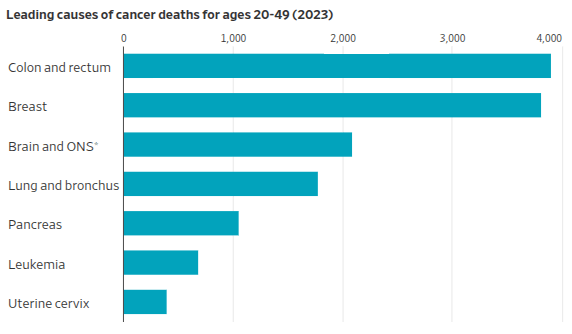

Colon cancer is now the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. for those under 50. Medical groups have lowered the recommended age for colonoscopies that can detect the disease while there are good odds for effective treatment.

_____________________________________