Inside a multistory office building in Manila’s financial district, around 60 young men and women monitored and controlled artificial intelligence robots restocking convenience store shelves in distant Japan. Occasionally, when a bot dropped a can, someone would don a virtual-reality headset and use joysticks to help recover it.

The AI robots are designed by Tokyo-based startup Telexistence, and run on Nvidia and Microsoft platforms. Since 2022, the company has deployed the machines in the back rooms of over 300 FamilyMart and Lawson stores in Tokyo. It is also planning to use them soon in 7-Elevens.

The bots are remotely monitored 24/7 in Manila by the employees of Astro Robotics, a robot-workforce startup. Japan faces a worker shortage as its population ages, and the country has been cautious about expanding immigration. Telexistence’s bots offer a workaround, allowing physical labor to be offshored. This lowers costs for companies and increases their scale of operations, he said.

It’s hard to find workers to do stacking in Japan. If you get one who’s willing to do it, it’s going to be very expensive. The minimum wage is quite expensive. It’s easy to get young, tech-savvy Filipinos to operate the robots. Each tele-operator, called a “pilot,” monitors around 50 robots at a time.

The bots are usually autonomous, but occasionally — about 4% of the time — they mess up. Perhaps they drop a bottle, which rolls away. Getting the AI bot to recover it by mimicking the human grip perfectly — the friction, the feel of metal in the hand — is one of the more challenging problems in robotics. That’s when a pilot steps in.

Astro Robotics’ tele-operators are benefiting from an AI- and automation-related boom in IT-service work and tech jobs in the Philippines, even as layoffs hit similar workers in richer countries. Filipino tech workers maneuver industrial robots, drive autonomous vehicles, collaborate with AI on various tasks, or help build “AI agents,” which are computer programs that enable autonomous action.

________________________

Diane has been a death doula for two decades now, meaning she is a companion for people at the end of life. She has sat beside people with no time left to waste and nothing left to prove, continually learning from the profound insights they leave behind. An insight she has gleaned:

What does it really mean to live like you are dying? Go skydiving? Ride a bull? Those may sound fun, but insights from people who are actually dying are often simpler and much deeper.

One client told me, “I just want to sit in my own kitchen one more time, with the people I love and a bowl of warm, fresh pasta with parmesan cheese melting on top.” That was his dream. Not a trip to Bali. Not bungee jumping. Just warm pasta, family, and home.

I used to expect that people would reminisce about big events like weddings, awards, or epic vacations. But over and over, what they actually longed for were the simplest pleasures.

My client Bernice had lived an extravagant life. Her walls were covered with perfectly posed photographs of big events from her life. But in her final months, she said, “I wish I had different pictures on the wall—messy ones. Pajama parties with friends, Sunday night movies with my kids, and neighborhood barbeques.” Those were the memories that stirred her soul.

We spend so much of life chasing big moments, but the dying often remind me that it’s not the grand gestures that matter most in the end. It’s the small, ordinary things. A meaningful life is built in everyday moments. Not in the highlight reel, but in the quiet, ordinary spaces in-between.

The dying know something we seem to have forgotten: Life is happening right now. In the warm pasta. During the neighborhood barbecue. In the sound of your favorite voice calling your name. Big events are wonderful, but in the end, the ordinary is everything.

____________________________________

The decline of local news has all kinds of implications. One that doesn’t get much attention is that the wider the news becomes, the more likely it is to be pessimistic. Two things make that so:

- Bad news gets more attention than good news because pessimism is seductive and feels more urgent than optimism.

- The odds of a bad news story—a fraud, a corruption, a disaster—occurring in your local town at any given moment is low. When you expand your attention nationally, the odds increase. When they expand globally, the odds of something terrible happening in any given moment are 100 percent.

______________________________________

The top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 account for 40% of the index’s market cap. Since ChatGPT launched in November 2022, AI-related stocks have registered 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth, and 90% of capital spending growth. Meanwhile, AI investments accounted for nearly 92% of the U.S. GDP growth this year. Without those AI investments growth would be flat. America is now one big bet on AI, and this concentration creates fragility.

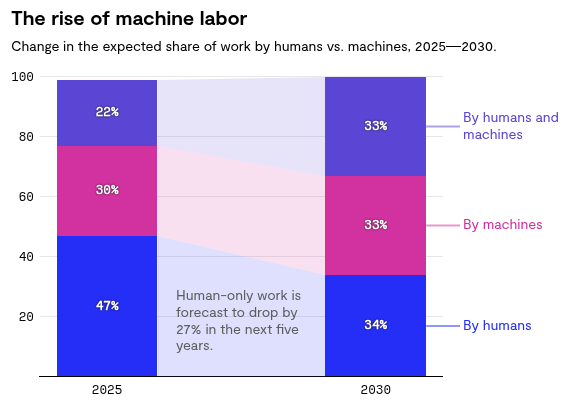

Valuations for the Mag 10 — the original group of seven leading tech stocks, plus AMD, Broadcom, and Palantir — are high, but not yet at historic peaks. The 24-month forward P/E ratio of the Mag 10 is 35x. In 2000, at the height of the dot-com bubble, the top 10 stocks traded at 52x forward earnings. Implicit in these valuations, however, is an assumption that AI will help these companies cut costs, or grow revenues by $1 trillion in the next two years. I believe we’re either going to see a massive destruction in valuations, infecting all U.S. stocks and global markets. Or we’re going to see a massive destruction in employment across industries with the highest concentrations of white-collar workers. Both scenarios are ugly.

_____________________________

Cellphone bans in schools have become a popular policy in recent years in the United States, yet very little is known about their effects on student outcomes. In this study, we try to fill this gap by examining the causal effects of bans using detailed student-level data from Florida and a quasi-experimental research strategy relying upon differences in pre-ban cellphone use by students. Several important findings emerge.

- The enforcement of cellphone bans in schools led to a significant increase in student suspensions in the short-term, but disciplinary actions began to dissipate after the first year, potentially suggesting a new steady state after an initial adjustment period.

- We find significant improvements in student test scores in the second year of the ban after that initial adjustment period.

- The findings suggest that cellphone bans in schools significantly reduce student unexcused absences, an effect that may explain a large fraction of the test score gains.