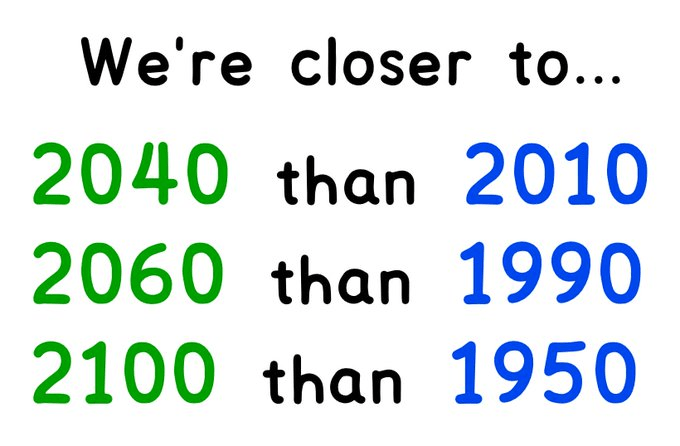

Some thoughts on time. Times we grew up envisioning as the far future aren’t so far away anymore. Even if lifespans stayed as they are now, many of today’s college students will live to see the 22nd century. Many of today’s babies will still be in the peak of their careers in the year 2100. And 2040, 2060, and 2100 are now closer to us than 2010, 1990, and 1950.

Likewise, much of what still feels like recent history is beginning to look a lot like ancient history. NSYNC’s “Tearing Up My Heart” came out closer to the moon landing than to today. E.T. hit theaters closer to the 1930s than to today. And Billy Joel’s “She’s Got a Way” was released nearer to World War I than the present moment.

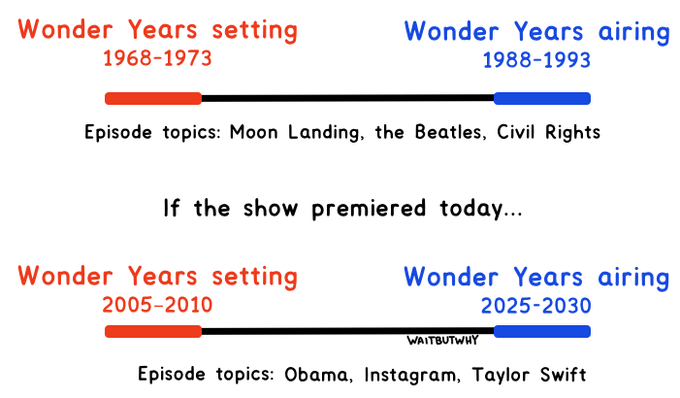

If Back to the Future were released today, Marty would be heading back to the ridiculously retro year 1995. His teenage parents would be doing hilariously old things like talking on big cell phones and hanging out in AOL chat rooms. And of course, no existential time crisis would be complete without The Wonder Years. The show aired from 1988-1993 and took place in the years 1968-1973. If the show debuted today, it would be set in 2005-2010 and cover nostalgic old things like Obama’s election, Instagram like counts, and Taylor Swift concerts.

___________________________________

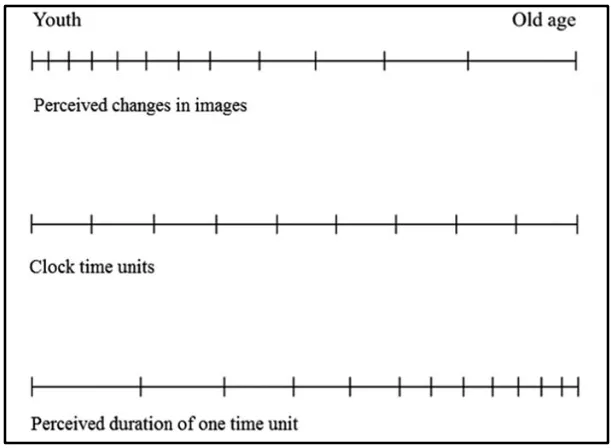

How to change our perception of time. Say the average lifespan is 80 years old. Then consider that time feels like it moves faster as we age. At age 40, the average person may be 50% through their biological life but they may have experienced 75% of what the brain will ever experience.

When you are looking back at the end of a childhood summer, it seems to have lasted for such a long time because everything was new. But when you’re looking back at the end of an adult summer, it seems to have disappeared rapidly because you haven’t written much down in your memory. So here is the take-home lesson. We have to seek novelty because this is what lays down new memories in the brain.

____________________________________

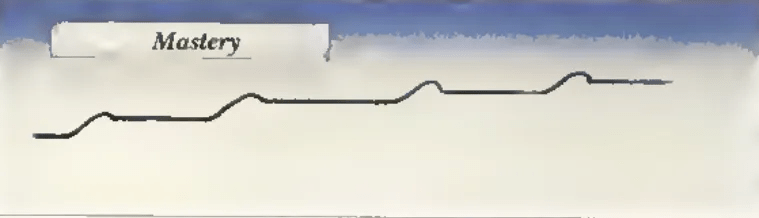

Jerry Seinfeld gave a great interview talking about what still drives him now that he has so much money. He talked about the importance of having a good skill, and he referenced an Esquire article from the late 1980’s that became the foundation for how he thinks about achieving mastery. It focused on things like plateaus combined with brief spurts of progress, the importance of having a child’s mindset and muscle memory.

____________________________________

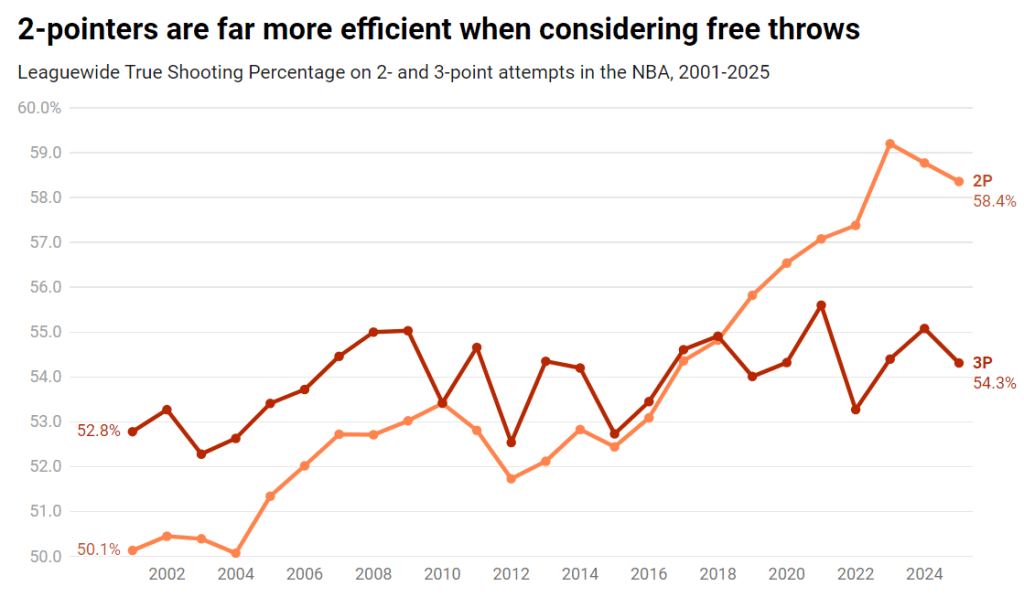

The argument for more NBA threes has always been the same: it’s math. The simple fact is that teams need only shoot 33 percent on 3-pointers to break even (in terms of points per shot attempt) against 50 percent on 2-pointers. But nothing stays static for long in professional sports. As the league’s brain trusts encouraged more and more threes, the efficiency of each shot type changed — and while 3-pointers have averaged a relatively steady level of points per field goal attempt for nearly two decades now, the 2-pointer has rapidly become more efficient, to the point that it has caught up to (if not surpassed) the efficiency of a 3-pointer:

This is even more the case when we consider that it’s much easier to get fouled attempting a 2-pointer than a 3-pointer.

____________________________________

52 Things Learned In 2024, including:

- Indian Americans own about half of all motels in the United States. Of them, 70% have the last name Patel.

- People know whether or not they want to buy a house in just 27 minutes, but it takes 88 minutes to decide on a couch.

- About 25% of the decline of casual sex among young men since 2007 can be explained by video games.

- It takes twice as long to cook a chicken today compared to 100 years ago because twenty-first century chickens get less exercise.

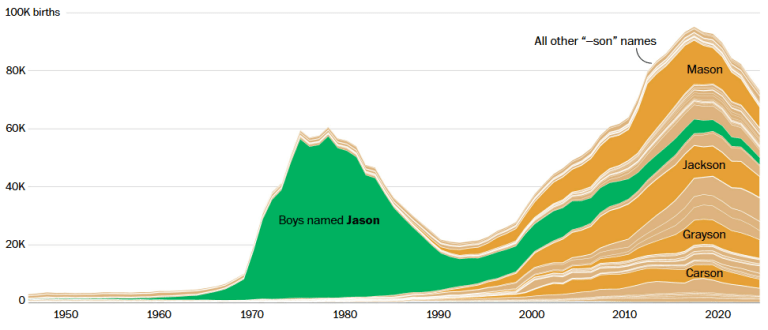

- American baby names trends shifted from family names a century ago to popular names a generation ago to popular endings today. A generation of people named Jason has given way to babies with -son endings: Mason, Jackson, Grayson, and Carson. Today, 48% of the top 500 baby names share only ten endings.

________________________________________

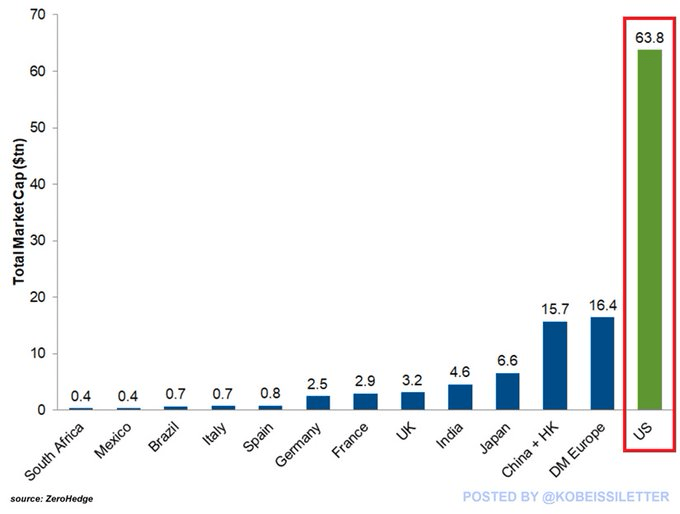

- The U.S. stock market is now worth $64 trillion and rising by the hour.

- The market cap has doubled in less than 5 years, and it added $10 trillion alone in 2024.

- China, Hong and all of Europe’s stocks combined are now worth less than 50% of U.S stocks.

- The U.S. Magnificent 7 alone are worth more than every single company in all of Europe.

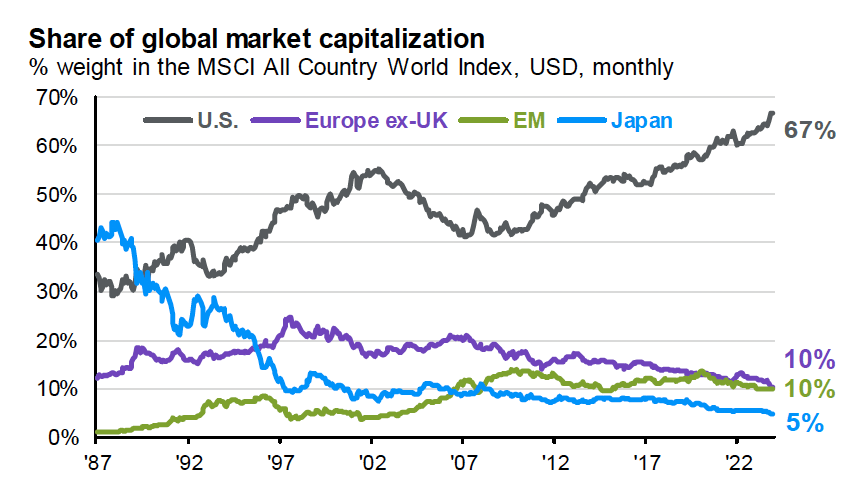

Zooming out to look at how we got here:

Dividends and share buybacks (total shareholder yield) in Europe and Japan are far more attractive than the U.S. A major reason for this is because you are paying an extraordinarily high price in U.S. stocks (vs. the rest of the world) for the yield you receive in return:

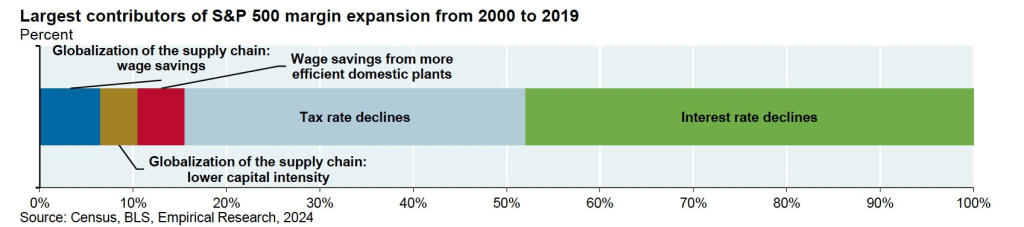

The largest contributors to the S&P 500’s (profit) margin expansion have come from taxes and interest rates declining. Let’s hope the U.S. government continues to have unlimited borrowing power at low interest rates to continue that trend forward:

___________________________________

Cliff Asness, the billionaire founder of AQR Capital, wrote this week what he thinks a “normal” money manager’s letter to clients will look like 10 years from now. He reviews, bonds, private credit, private debt, liquid alts, crypto and other sectors, but I thought his sections on U.S. and international stocks was interesting:

U.S. Equities (letter to clients on January 2, 2035):

First, it turns out that investing in U.S. equities at a CAPE in the high 30s yet again turned out to be a disappointing exercise, Today the CAPE is down to around 20 (still above long-term average). The valuation adjustment from the high 30s to 20 means that despite continued strong earnings growth, U.S. equities only beat cash by a couple of percent per annum over the whole decade, well less than we expected.

International Equities (letter to clients on January 2, 2035):

Of course, after being left for dead by so many U.S. investors, the global stock market did better with non-U.S. stocks actually turning in historically healthy real returns (like 5-6% per annum over cash). It turned out that, just as we thought, the U.S. really did have the best companies (most profitable, most innovative, fastest growing) and this indeed continued in this last decade. But it also turned out that paying an epic multiple for the U.S. compared to the rest of the world mattered somewhat more than we thought, and international diversification, as we knew it would one day, did eventually work. It turns out there was indeed a price at which European stocks made sense. That was news to us. Luckily, we removed non-U.S. stocks from our benchmark back at the beginning of ’25 so this differential did not affect our benchmark-relative performance this last already painful decade, only our, well, you know, actual performance.