Happiness, it turns out, is more Rorschach than road map. Is it found in the ultraluxe wellness center or the austere monastery? Does it come from getting what you want or wanting less?

By the early 20th century, utility maximization — happiness writ small — emerged as a linchpin of economic analysis. Public happiness, in turn, became a matter of optimizing the sum of individual welfare. The mathematics could be complex, but the premise was simple: Getting what you want in life — that’s happiness, bro.

The notion of happiness as choice-making swiftly migrated from economic models into the marrow of the broader culture. What was once a lifelong project shrank into a sequence of transactions. As the midcentury economy boomed, it didn’t just build wealth; it reconstructed desire. The good life, formerly the province of philosophers, was now a mainstay of the marketers: happiness packaged as the perfect lawn, the gleaming automobile, the immaculate kitchen with its humming refrigerator. We became, almost without noticing, what we bought.

And if you still felt empty? That’s where the therapy culture of the 1970s and 1980s came in — not as a remedy for consumerism but as an extension of it. The older vocabulary of life-defining commitments and meaning-making projects continued to wither while a new lexicon took hold: self-acceptance, self-esteem, self-love.

By the 1990s, happiness had acquired a personal brand. Oprah Winfrey presided over a daytime academy of self-care, empowerment and curated aspiration. Then came the next wave: the life-hacking, self-quantifying, habit-stacking era of optimization gurus like Tim Ferriss, whose first book, published in 2007, was “The 4-Hour Workweek” — “a toolkit,” in his words, “for maximizing per-hour output.”

Excitement is the more practical synonym for happiness, and it is precisely what you should strive to chase,” Ferriss wrote. “It is the cure-all.” Amid the excitement, the happiness concept kept getting miniaturized. With the rise of the algorithms, decision-making became a series of bite-size transactions. If you liked this, you’ll like that. Every swipe, click and purchase was an act of preference revelation, the digital cookie crumbs of personal identity.

In today’s social media ecosystem, happiness even threatens to become a ring-lighted aesthetic: matcha lattes, artisanal candles, sage-smudging, captioned reminders to just breathe. Once again, happiness is work — but now the work of packaging moods and moments for validation, with a tiny dopamine hit for each “like.”

“So long as you’re happy,” parents tell their kids. In reality, they want to see their children engaged in something worthwhile, contributing to something beyond their own fleeting satisfactions.

If you’ll indulge the philosophers’ habit of conjuring characters to illustrate their abstractions, imagine a young person — let’s call her Julia — who left community college after a semester and has bounced between gigs ever since: dog-walking, cafe shifts, warehouse nights. Her life is messy, but she has learned how to show up for people. When her neighbor’s mother gets sick, Julia brings groceries. When her cousin gets out of rehab, she’s the one who texts every day. She doesn’t have a wellness routine or a five-year plan. But people trust her. She holds lives together in small, invisible ways.

Or imagine a middle-aged man named Daniel, a product manager with a smart fridge and an Optimal Morning Routine. For years, he has chased happiness through upgrades — to his apps, his appliances, himself. But lately, the returns feel thin. When his niece’s soccer team needs a coach, he volunteers, awkwardly at first, then with growing investment. Daniel has started showing up at town meetings, fighting to save the field from developers. Now his calendar includes something he cares deeply about that doesn’t come with a progress bar.

Daniel still wears a Whoop band. Julia hasn’t found her “calling.” But they’re living into a broader idea of happiness — less about what they have, more about what they give, who they’re with, what they’re part of.

Is it possible that happiness stayed big, and it’s only our way of talking about it that got small? Surely the old understanding, in which the pursuit of happiness is inseparable from shared commitments, hasn’t gone anywhere. On some level, we still know the difference between feeling good and flourishing, between the hedonic and the eudaemonic, between the algorithm’s next suggestion and the difficult and uncertain path toward a meaningful existence. Yes, we often speak as if feelings are all that count, but maybe that’s because the language of the “good life” has been hollowed out.

____________________________

Inversion is a mental model that flips the script on traditional problem-solving. Rather than look at a problem in a linear, forward, logical manner, you think about it in reverse. Well, there is one complex, foundational problem that is truly universal: How do you live a good life? Using inversion to address it: Here are some ways to live a miserable life…

- Allow idleness to dominate your life – Stress and anxiety feed on idleness. They take hold while you sit and scroll on your phone, while you overthink your situation, while you compare yourself to others, while you try to create the perfect plan. When you take action, you starve them of the oxygen they need to survive.

- Allow optimal to get in the way of beneficial – Ambitious people have a bad tendency to think like this: “I don’t have an hour to work out, so I just won’t go. I don’t have two hours for deep work, so I’ll do email instead. I don’t have 30 minutes to call my mom, so I won’t call at all.” When you allow optimal to get in the way of beneficial, you ignore the most powerful principle in life: Anything above zero compounds. A little bit is always better than nothing. Tiny wins stack over long periods of time. Small things become big things.

- Obsess over speed – Life is about direction, not speed. It’s much better to climb slowly up the right mountain than to climb fast up the wrong one.

____________________________

More police officers kill themselves every year than are killed by suspects. At least 184 public-safety officers die by suicide each year, while an average of about 57 officers are killed by suspects. Law-enforcement officers are 54 percent more likely to die by suicide than the average American worker.

Most officers are required to pass psychological and physical screenings before they are hired. But many struggle after chronic exposure to trauma. Police officers have higher rates of depression than other American workers. Shift work, which disrupts sleep, and alcohol use, long the profession’s culturally accepted method of blowing off steam and managing stress, further compound health issues.

______________________________

A survey of 1,000 managers across America revealed the reasons that 8 in 10 managers said newly hired college graduates did not work out during their first year on the job:

- 78%: Excessive use of cell phones – the top pet peeve of managers

- 61%: Entitled or easily offended

- 57%: Unprepared for the workplace

- 54%: Lack of a work ethic

- 47%: Poor communication skills

- 27%: Lack of technical skills

Other concerns managers had about the graduates included lateness, failure to turn in assignments on time, unprofessional behavior, and inappropriate dress and language.

Colleges don’t teach students how to behave in the workplace, and there is a lack of transitional support from both universities and employers. Most students graduate with little exposure to professional environments, so when they arrive at their first job, they’re often learning basic workplace norms for the first time.

______________________________

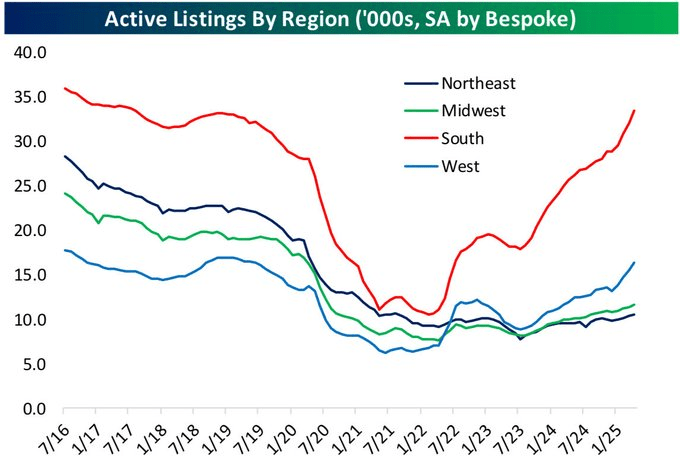

Where the number of homes for sale is growing. Fast.

___________________________

The Russell 1000 is a stock market index that represents the 1,000 largest companies in the U.S. by market value (also called market capitalization). The graph below shows the number of stocks within that 1,000 that fall by a certain percentage over a 1, 3 and 5-year time frame. While over time most major indices like The Russell 1000 go up, the odds are very high that any individual stock is going to fall by a lot.

___________________________

Lead characters were far more likely to die in the 1960s and 1970s than they are today. Across the 1970s, almost one in three protagonists died by the end of the film. That rate has steadily declined since. The drop has been particularly sharp since 2010. In the last five years, the share of lead characters who die has averaged just 17%. This is one of the lowest rates in almost a century of film history.

_________________________________

____________________________

Only 21% of American college revenues come from tuition:

__________________________

The average age of the global population is up from 26.5 years in 1980 to 33.6 years in 2025. Meanwhile, the average growth rate of the global population has also halved, from 1.8% in 1980 to 0.9% in 2025. The growth rate is expected to hit zero by 2084, and the world’s population is expected to begin declining by 2085, with the average age rising to 42. At the end of the 21st century, the average age is projected to be 43 years.