Vikram Mansharamani published his global developments to watch from 2026 to 2031. These were a few that I found interesting:

- Bio-fabrication technologies advance rapidly enabling human organs to be printed on demand. A new industry of “body mechanics” emerges and utilizes AI-driven prediction models to pre-emptively replace joints, bones, and organs before they fail. The expected lifespan of a child born in 2030 rises to 151 years.

- Advancements in quantum computing lead to a geopolitical crisis as all formerly- secure communications become instantaneously vulnerable. Each breakthrough leads to a bump in gold prices as investors fear the possibility of quantum-enabled theft of cryptocurrency. Cybersecurity re-emerges as an area of top concern for corporate boardrooms, nation states, and individuals.

- Deepfake technologies become indistinguishable from real life, leading to mass human confusion and cognitive dissonance. Reality Defender emerges as the world’s hottest company as it secures elections by providing voters assurance of authentic messaging from candidates, thereby saving democracy from being hijacked by technologically-savvy foreign actors.

- A boom in next generation nuclear technologies combines with improved hydrocarbon extraction efficiency to keep energy prices contained in the face of exploding demand from technology applications and data centers. As copper emerges as the world’s most strategic resource, the Great Powers shift their focus from the Middle East to the Andean region.

- The insatiable consumer appetite for protein continues indefinitely. Restaurants start disclosing the protein content of menu items, and Coke introduces a high-protein soda. Public health deteriorates as Americans’ religious focus on protein leads to elevated consumption of sugars and artificial sweeteners.

- The global use of GLP-1 drugs skyrockets as an oral pill becomes readily available and is covered by most health insurance plans or government health offices.

- Artificial intelligence generates deflation, leading to structurally rising unemployment and elevated debt levels.

___________________________________

We are drowning in information and data. So much so that we’re obese in the mind. The same way the human body was not prepared for a world of abundant food, and we thus transformed our cities into feeding zones full of fat people, the human mind is not prepared for a world with infinite content and information. Less than two decades into social media and the world is already full of morbidly obese minds that cannot think or focus, let alone produce anything novel anymore.

Even the best of us are mentally overweight! There are few, if any, original ideas anywhere. Everyone, everywhere is in a constant, social-media induced mimetic trance, mistaking repetition for thought while parroting the same words as those in our little echo chamber.

The only solution is to shut it all out. I’ve come to the realization that selective ignorance on the other hand; I’m talking actual willful, intentional ignorance, is not only blissful, but is a holy virtue.

It’s the kind of ignorance that is deliberately oblivious to what is going on in the world because none of it matters an iota in the grand scheme of one’s life. It’s the kind of noble, savage and ruthless ignorance that doesn’t even waste energy saying: “I don’t care.” It’s just blissfully above to the noise, present only with what matters, here and now.

As the pace of things accelerates and the never ending cycle of hysteria continues, it’s dawned on me that none of it really matters. Sure, individual events may matter to some people, but because of how we’re wired and how the internet and social media have connected us all, the number of events that can (a) happen and also (b) be brought to our attention is infinite.

Which in short means that everything matters all the time. But when everything matters all of the time, then the only reaction for the mind and body is to become numb. In other words, nothing means anything or matters any more. This is not a way to live.

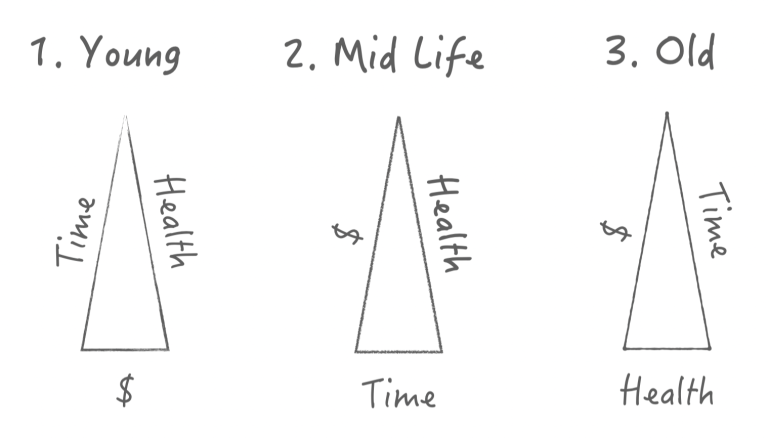

Attention, at the end of the day, is all we really have. It’s finite. It’s super super super finite. We have so little time. We have only so much energy. It’s hard to focus at the best of times, and here we are, on a daily basis, being either:

- Distracted by things inside of a phone-size shopfront that most of us will either never have (picture-perfect women, hotels, cars, etc), or

- Inflamed by things on that same stupid screen which we have no relationship to or influence over, happening in other parts of the world, thousands of miles away.

The end result of all this stupidity (for 99.9999% of people) is just a LOSS of attention. I’m sure some of you have found inspiration or motivation from these screens (this can happen), but if we’re all being TRULY honest with ourselves here, we can admit the truth: we can be just as inspired by a walk on the beach or a conversation with a loved one too.

When I’m on my deathbed, I won’t remember wtf I saw on Twitter or Instagram from all those endless hours of looking at the screen. But I will remember the time I spent with the people who I truly loved. To find a solution, one must first understand the problem, and the problem is twofold:

- Nobody is entirely immune to the siren call of dopamine. These platforms hack your biology in such a way that they hook you. Thus you are not fighting the platform, but your own biology – and this consumes energy. Energy that could be much better spent elsewhere.

- Our cups are already full. Those of use who are strong learners have already had our fill, especially if you’ve been online for the last 5 – 10 years. We’re well past the point of diminishing returns. We have all the information we could possibly need to live and lead meaningful lives. Stuffing our minds with more stuff won’t improve anything, and at this point is just a distraction from living in the real world and implementing the things we’ve already learned or know.

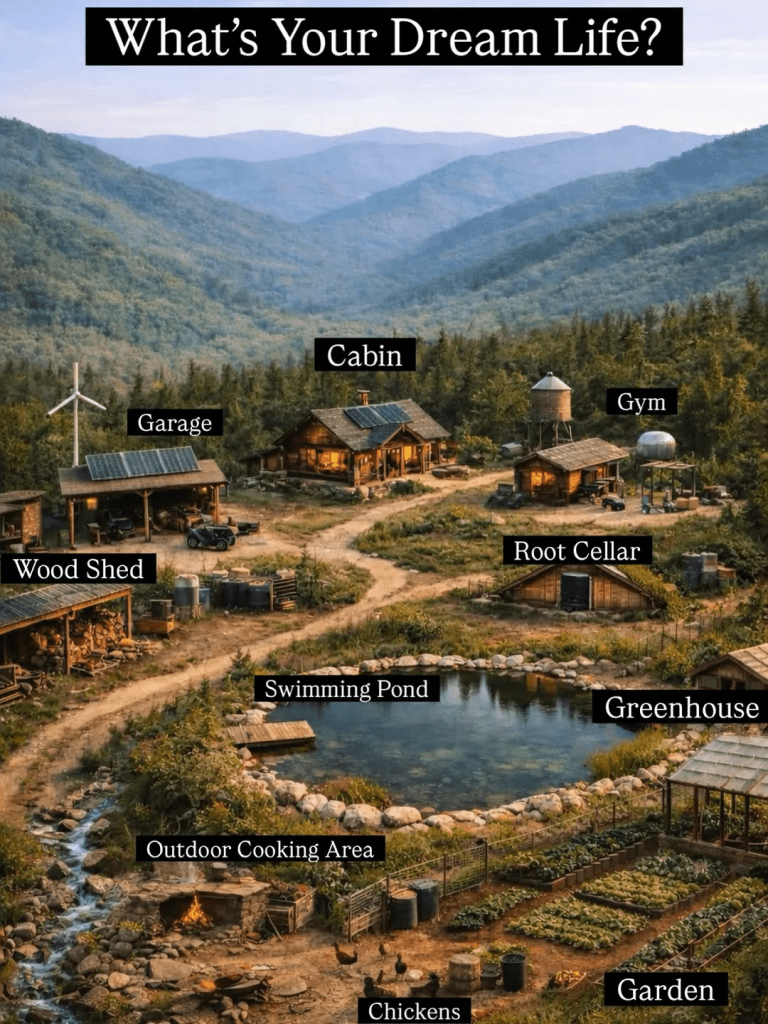

The beautiful thing about value is that it always migrates to the zone of greatest scarcity. As a zone attracts more attention (and thus value), it begins to lose scarcity, until it gets saturated, and then one day, the value migrates away to a zone where scarcity prevails. People are starting to realize that being online is quickly becoming uncouth and that they need to run away. But where?