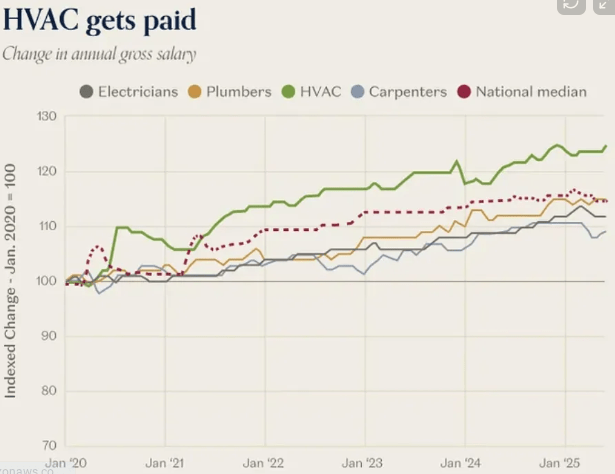

Weird things happen to economies when you have huge bursts of productivity that are concentrated in one industry. Obviously, it’s great for that industry, because when the cost of something falls while its quality rises, we usually find a way to consume way more of that thing – creating a huge number of new jobs and new opportunities in this newly productive area.

But there’s an interesting spillover effect. The more jobs and opportunities created by the productivity boom, the more wages increase in other industries, who at the end of the day all have to compete in the same labor market.

Our explosion of demand for data centers means there’s infinite work for HVAC technicians. So they get paid more (even though they themselves didn’t change), which means they charge more on all jobs (even the ones that have nothing to do with AI). Furthermore, the next generation of plumber apprentices might decide to do HVAC instead; so now plumbing is more expensive too. And so on.

_______________________________

Academics have published new research on the impact that Short Form Videos (SFV) like TikTok, Instagram Reels and Youtube shorts have on cognitive and mental health. The report systematically reviews and analyzes 71 studies involving over 98,000 participants.

- SFV use is linked to poorer cognitive performance, with the strongest deficits in attention and inhibitory control, suggesting users struggle to focus and suppress impulses.

- Frequent exposure to fast-paced, highly rewarding SFV content may rewire attention systems, fostering “rapid disengagement” from tasks that are slower or require sustained effort, reducing cognitive endurance over time.

- SFV use is associated with poorer overall mental health, with the strongest links to stress and anxiety, indicating consistent emotional strain among heavier users.

- Heavy SFV use reinforces impulsive engagement loops driven by dopamine rewards, contributing to compulsive scrolling and difficulty disengaging, patterns resembling behavioral addiction.

- Short-form video consumption is associated with poorer sleep quality, especially when used at night, due to overstimulation and blue light disrupting melatonin, which can worsen mood and cognitive functioning.

- Higher SFV use correlates with increased loneliness and reduced life satisfaction, as digital interactions replace real-world social connection for some users.

- Negative effects occur across both youth and adults, meaning the cognitive and emotional risks of SFV use are not limited to developing brains; adults experience similar declines and mental health associations.

_______________________________

These days, it’s all stocks all the time, with reputable authorities calling on small investors to put everything they have saved into equities. Older investors are reminded of the mantra so common in 1999: “Every penny you don’t have invested in stocks will hurt you.”

More than a generation ago, financial historian Peter Bernstein wrote about investors’ “memory banks,” the market experience that accumulates in their hippocampi over their investing lives and molds their investment strategy. As he put it, looking back on the 1990s: “Most of the new participants in the market had no memory of what a bear market was like.”

And here we are today, almost seventeen years into a great bull market. Rather like 1999, also seventeen years into a long-term bull market, or 1966, once more seventeen years. Or 1873, sixteen years in, or 1837, eighteen years in, or 1893, twenty years in — to name a few of the notable tops over the past two centuries. Just long enough to produce empty memory banks in just enough investors.

A new generation of investors have never personally experienced a long-term bear market. Their memory banks are devoid of the damage wrought by the Grim Reaper of equity risk. Let’s be generous and assume some have read market history and know that stocks can lose money — sometimes, a lot — and take months, if not years, to recover. There’s a difference, though, between being told that markets can fall by more than 50% and having it burned into your memory banks by seeing your net worth halved in real time as the economy careens towards the precipice.

_____________________________________

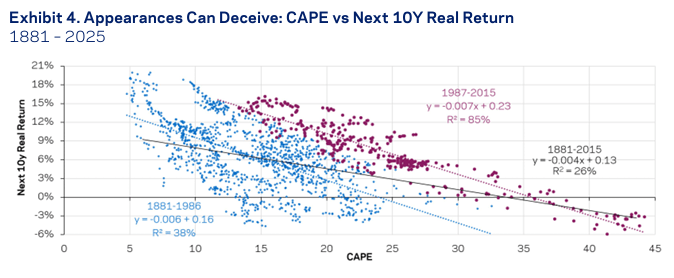

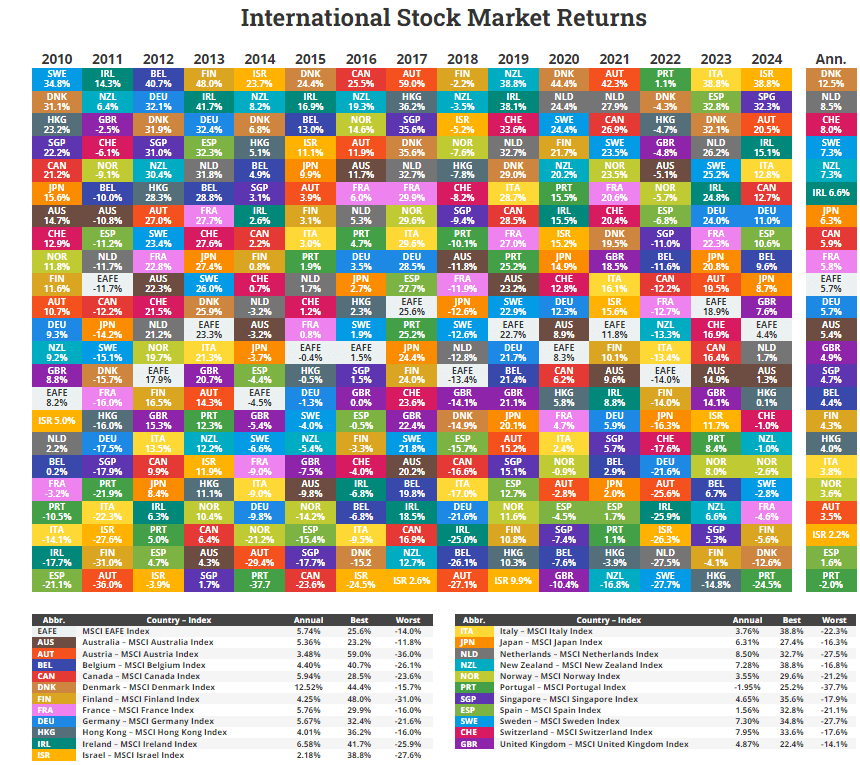

Historically, valuations have been a useful (though not perfect) indicator of real returns over the following decade. Below, you’ll see historical CAPE readings (in black) for the U.S. market alongside their corresponding forward ten-year real returns (in green). The conclusion is straightforward: when valuations are low, future returns tend to be above average; when valuations are high, forward returns tend to be much more muted.

Right now, the U.S. market sits at a CAPE ratio of around 40. It’s nearly double the long-term average of roughly 20, and the second most expensive in history.

historically, when valuations have climbed to this level, the following decade hasn’t been kind to investors. Not once has a country that ended a year with a CAPE above 40 produced positive real returns over the next ten years. That’s not a personal opinion but what the data shows.

To get a sense of what current valuations might mean going forward, I ran a linear regression using historical CAPE data and forward ten-year real returns. The relationship is remarkably consistent: as valuations rise, future returns fall. At today’s valuation levels, the regression suggests an expected real return of -2.46% for the next decade. From a historical perspective, the last time we were at the CAPE reading we find ourselves in today, the market went on to lose -2.11% per year for the next ten years.

Valuation isn’t the only red flag flashing. Today, about 40% of the market is concentrated in its 10 largest companies. This is the most concentrated the market has ever been.

Concentration itself isn’t a bearish sign. What really matters is how concentration changes going forward. Rising concentration tends to coincide with strong market performance as leading firms continue to gain share and deliver growth. On the other hand, when concentration starts to fall, this means your largest players are underperfoming the rest of your portfolio, and that’s when returns have historically suffered. If the biggest names continue to pull away from the pack, the market could remain strong for a while. But if that leadership falters, history suggests the unwind can be painful.