Contemplating death is the New Year’s resolution to end all resolutions. Why? Because it sharpens our focus, allows us to clarify what truly matters—and to craft our goals and priorities around that—anchors us in the present moment, and deepens our appreciation for all that life has to offer, right here and now.

Remembering that we are going to die goes hand-in-hand with another key realization: we have no way of knowing how much time we have left. We might die in three years, or 38 years, or a few months from now. So, what should we do with the time we have—with our one wild and precious life?

Humans have long known of the power of this practice. We’ve been contemplating death for over 100,000 years, from the earliest archeological burial artifacts to Buddhist maraṇasati, from Stoic philosophy to ancient Egyptian funerary texts.

It’s only in the modern Western world that we began to see this practice as depressing or morbid. We lost our relationship with death, and somewhere along the way, we stopped living fully too.

Here are 11 science-backed benefits of taking the time to think about death:

- Cut through your own bullshit – helps you overcome excuses and stop wasting time on what’s not serving you

- Clarify your values – less bullshit = more clarity

- Motivation to act – gives you permission to stop living on autopilot or within societal expectations and start living in alignment with what actually feels true

- Find a deeper purpose – research shows that being reminded of our mortality triggers a psychological drive to seek or restore meaning in life.

- Be more present – when you fully accept that everything, and I mean everything, will ultimately be taken from you, the present moment suddenly becomes sacred

- Gratitude – like anything else rare and precious, when we remember that life is fleeting, we value it more

- Stronger relationships – when you remember that one day, everyone you love will die, and so will you, your relationships change

- Empathy and compassion – death is the great equalizer

- Unlocks creativity – gives rise to an intense drive to make your own little dent on the universe, to leave something behind to say that you were here.

- Keep your ego in check – it’s a reminder that you’re not the center of the universe, the desire to impress starts to dwindle, liberating you from feeling like you need to be the smartest, best, most admired person in the room – instead, you start to show up as a real person: flawed, fleeting, and free

- Take more risks – the only thing scarier than dying is never having really lived, so you’re more likely to pursue the life you’ve been dreaming of.

______________________________

Interest rates have begun to come down. Inflation has mostly subsided, and the real economy is still doing decently well. So why are American consumers more pessimistic than they were during the depths of the Great Recession or the inflation of the late 1970s?

It’s possible to spin all sorts of ad hoc hypotheses about why consumer sentiment has diverged from its traditional determinants. Perhaps Americans are upset about social issues and politics, and expressing this as dissatisfaction about the economy. Perhaps they’re mad that Trump seems to be trying to hurt the economy. Perhaps they’re scared that AI will take their jobs. And so on.

Here’s another hypothesis: Maybe Americans are down in the dumps because their perception of the “good life” is being warped by TikTok and Instagram.

I’ve been reading for many years about how social media would make Americans unhappier by prompting them to engage in more frequent social comparisons. In the 2010s, as happiness plummeted among young people, the standard story was that Facebook and Instagram were shoving our friends’ happiest moments in our faces — their smiling babies, their beautiful weddings, their exciting vacations — and instilling a sense of envy and inadequacy.

However, note that during the 2010s, consumer confidence was high. Even if people were comparing their babies and vacations and boyfriends, this was not yet causing them to seethe with dissatisfaction over their material lifestyles. But social media today is very different than social media in the 2010s. It’s a lot more like television — young people nowadays spend very little time viewing content posted by their friends. Instead, they’re watching an algorithmic feed of strangers.

There were rich people like that in 1920, or 1960, or 1990. But you almost never saw them. Maybe you could read about them in People magazine or watch a TV show about them. But most people simply didn’t have contact with the super-rich. Now, thanks to social media, they do.

But even more subtle might be the influencers who are merely upper class rather than spectacularly rich. These people aren’t living the lifestyle of a ultra-rich influencer, yet most of what you’re seeing in these photos and videos is economically out of reach for the average American.

These are not obviously rich people — they’re more like the 5% or the 1% than the 0.01%. Their lifestyles are out of reach for most, but not obviously out of reach. Looking at any of their videos, you might unconsciously wonder “Why don’t I live like that?”.

Americans were always shown examples of aspirational lifestyles on TV shows. Yet on some level, Americans might have realized that that was fiction; when you see a lifestyle influencer on TikTok or Instagram, you feel like you’re seeing simple, bare-bones reality.

The rise of social media influencers has scrambled our social reference points. Humans have always compared ourselves to others, but before social media, we compared ourselves to the people around us — our coworkers, friends, family, and neighbors.

Those classic reference points tended to be people who were roughly similar to us in income — maybe a little higher, maybe a little lower, but usually not hugely different.

But perhaps even more importantly — we were able to explain the differences we saw. In 1995, if you knew a rich guy who owned a car dealership, you knew how he made his money. If you envied his big house and his nice car, you could tell yourself that he had those things because of hard work, natural ability, willingness to accept risk, and maybe luck. The “luck” part would rankle, but it was only one factor among many. And you knew that if you, too, opened a successful car dealership, you could have all of those same things.

But now consider looking at an upper-class social media influencer. It’s not immediately obvious what they do for work, or how they could afford all those nice things.

Not only can you not explain the wealth you’re seeing on social media, but you probably don’t even think about explaining it. It’s just floating there, delocalized, in front of you — something that other people have that you don’t. Perhaps you make it your reference point by default, unconsciously and automatically.

___________________________

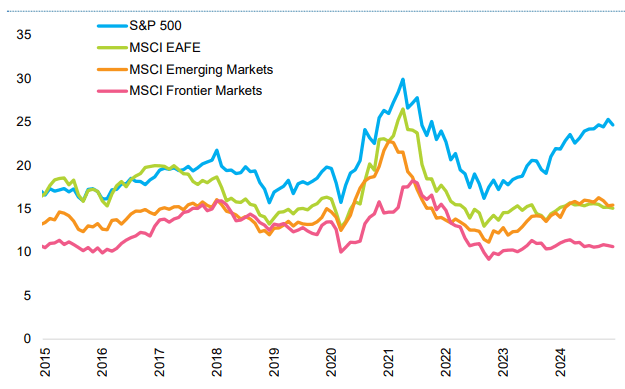

Frontier markets represent the world’s least developed investable economies,

offering exposure to countries with young populations and high economic growth

potential, yet smaller, less liquid markets. Over time, the composition of the MSCI

Frontier Markets Index has shifted meaningfully, with Gulf countries like Kuwait and

Qatar having “graduated” to emerging status and Asian and European nations now

taking greater prominence. Frontier markets remain dominated by financial services,

with larger weights to real estate, energy, and materials, reflecting other structural

differences compared with emerging and developed markets.

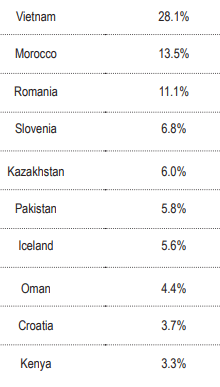

The MSCI Frontier Markets index is one of the most widely used indices related to

frontier markets. It contains approximately 238 stocks spread across 28 countries.1

The top three countries in the benchmark were Vietnam, Morocco, and Romania,

which collectively accounted for just over 50% of the index.

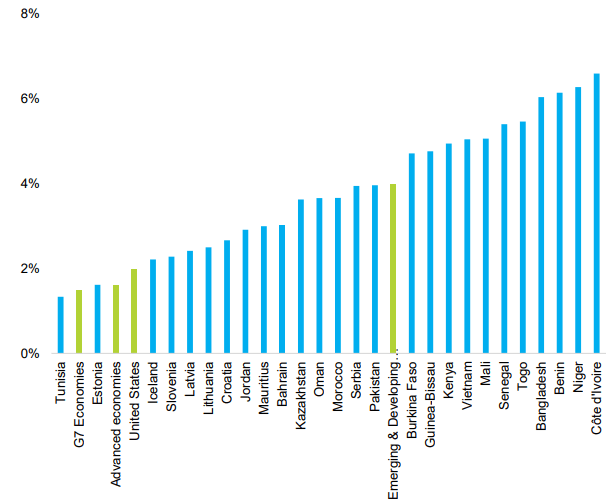

To better understand how growth expectations within frontier markets compare

with growth across the world, it is helpful to compare their GDP growth rate

expectations to developed and emerging markets.

Despite their strong expected GDP growth rates, frontier markets have not translated

that economic momentum into equivalent corporate earnings performance. Earnings

per share growth has stagnated even as valuations have remained low relative to

developed and emerging markets. This combination presents both opportunities

and risks. Value-oriented investors may find attractive entry points, but persistent

structural inefficiencies and volatility underscore the need for careful analysis.

_______________________________

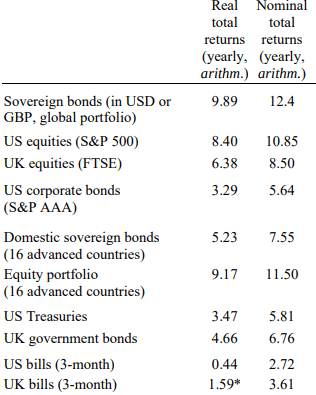

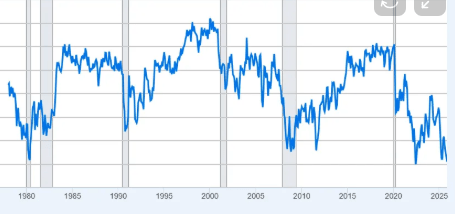

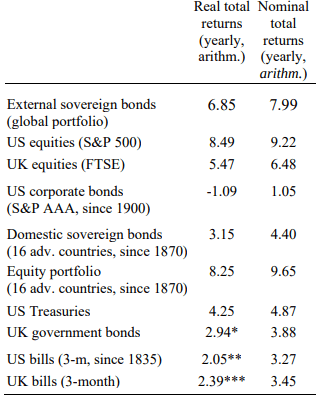

We compiled a new database of 266,000 monthly prices of foreign-currency government bonds traded in London and New York between 1815 and 2016, covering up to 91 countries.

Our main insight is that, as in equity markets, the returns on external sovereign bonds have been sufficiently high to compensate for risk. Real ex-post returns average more than 6 percent annually across two centuries, including default episodes, major wars, and global crises.

This represents an excess return of 3-4 percent above US or UK government bonds, which is comparable to stocks and outperforms corporate bonds. Central to this finding are the high average coupons offered on external sovereign bonds.

1815 – 2016:

1995 – 2016: