A few highlights from one of the best articles I’ve read this year discussing the private equity/credit bubble:

The golden age of Private Equity – at least from the standpoint of investor returns (FUM and thus fees to sponsors were significantly lower) – was during 1980-2000, and at a slight stretch, to around the time of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. During this era, PE delivered legitimately good returns – in some cases outstandingly so. What enabled it was that it was still a niche industry where there was a limited amount of capital chasing deals, while the backdrop was conductive.

In contrast to the 1980-2000s, private equity funds from the 2010s began paying a premium to public market valuations for (typically) small, subscale and illiquid businesses. The problem was that the same thing that always happens when too much money floods into an area happened – bidding competition heated up, target prices rose, and the opportunity that previously existed rapidly disappeared (though the vehicles’ high fee structures of course remained firmly intact). Not surprisingly, since the 2010s, and perhaps as far back as 2006, outcomes have dramatically changed, and PE has delivered generally disappointing returns and underperformed listed equities, and the magnitude of that underperformance has significantly worsened since 2022.

Warren Buffett has scrutinized PEs return calculations and found them to be “well, they’re not calculated in a manner that I would regard as honest.” All kinds of tricks can be and are used to inflate apparent relative returns. PE will often lock up commitments from investors years in advance, and only “call” the funds much later after a deal is done. The IRR calculations only include the period during which the funds are working, but investors need to keep cash in reserve as it can be called at any time, meaningfully diluting effective returns to investors.

The much bigger elephant in the room – the PE industry is currently “marking to model” and is sitting on a vast number of assets it is unable to sell – even in a bull market – because the marks are unrealistic. This will be meaningfully inflating claimed trailing returns, which remain mostly unrealized.

If you look at who private equity companies hire, it is typically ex investment bankers. These guys are deal makers and spreadsheet jockeys, not operational people, and there is no reason to believe they have any unique insights on the intricacies of running small, niche businesses, where specialized skills and decades of domain experience generally count for a lot more than general smarts.

Not to mention that as the industry has mushroomed in size, the average quality of the average hire has meaningfully degraded. Investment bankers also generally lack investment acumen. They are deal makers – a different skill set entirely.

Going even a step further – it’s probable that private equity ownership not only fails to deliver operational improvements, but very likely on net makes the operational performance of companies worse, particularly in the long term. The most obvious means by which this occurs is by saddling investees with significant levels of debt, as well as implementing wholesale asset stripping (such selling and leasing back real estate) and cutting operational costs and capital expenditures to the bone. They frequently don’t just cut the fat, but the muscle as well.

If you are apt to under invest and run the business for maximum cash extraction in the near term, jacking up prices, lowering service quality, squeezing employees, alienating customers and opening the door to competitor inroads – it may improve near term cash generation, but it often comes at the cost of long-term value degradation.

PE has now taken over a large portion of Las Vegas, for instance, and visitors routinely complain of high prices, poor customer service, and the removal of perks such as free drinks that previously endeared visitors to the strip. Visitation has been waning, and people complain Vegas has lost its charm, and has become overpriced and soulless, a victim of “corporate greed.”

This is far from the only example. Employees and customers of PE backed hospitals and dental practices often complain of declining service standards, high prices, and a significant increase in unnecessary treatments unethically prescribed to boost near term utilization/billing.

The fair value of the combined $5 trillion of assets held in the US Private Equity/Credit industry is probably worth only about 60% of that in reality – a $2 trillion hole. When that hole is exposed, it will change economic behavior, and likely to a noticeable degree.

Private Equity/Credit: The Bubble & Its Implications

________________________________

Great article from Nate Silver this week on reasons why there is more scoring in the NFL:

(1) The number of 55+ yard field goals has increased by 3x since just 2022:

(2) Between longer field goals and the dynamic kickoff, the field has basically been shortened by 10-15 yards.

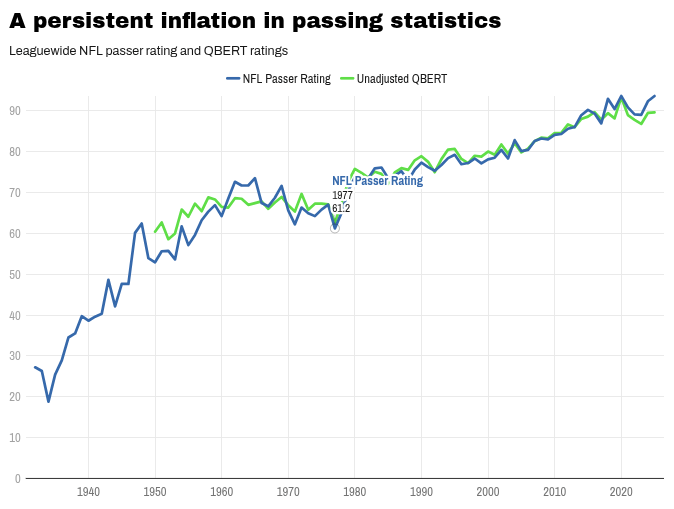

(3) Quarterback passer ratings are tied for their highest-ever at 93.6:

(4) For the first time in NFL history, quarterbacks as a collective are gaining enough rushing yards to outweigh the yards they lose from sacks:

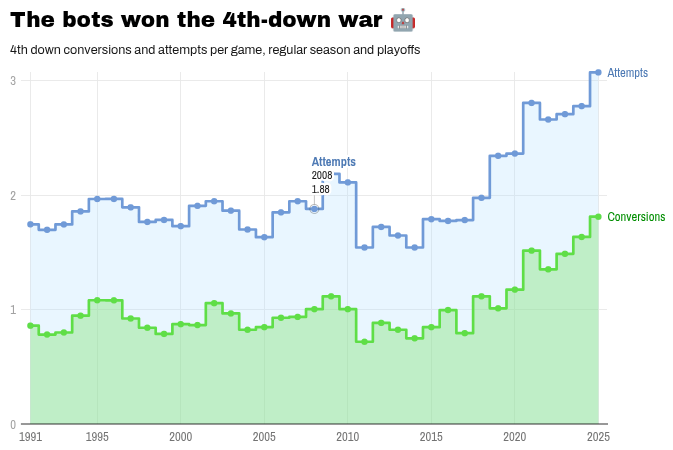

(5) Analytics have teams successfully attempting and completing fourth down conversions:

(6) Rushing plays on 4th-and-short are being attempted (and succeeding) at extremely high rates. The tush push effect:

_______________________

If you’ve ever received a spammy text falsely alerting you to an unpaid toll or failed delivery, it might have come from a so-called Phishing-as-a-Service network that Google is now trying to take down. In just 20 days, Google alleges, Lighthouse was used to spin up 200,000 fraudulent websites to attract over a million potential victims. It estimates that somewhere between 12.7 million and 115 million credit cards in the US were compromised by the scam.

In this alleged scheme, the text would link to a spoofed USPS page asking a user to enter their personal and payment details. The page tracks users’ keystrokes, according to the complaint, so the information is compromised even if the user has second thoughts before submitting.

__________________________

When Will We Make God? The key driver of the AI Bubble:

Hyperscalers (Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Oracle, IBM) believe they might build God within the next few years. That’s one of the main reasons they’re spending billions on AI, soon trillions. They think it will take us just a handful of years to get to AGI—Artificial General Intelligence, the moment when an AI can do nearly all virtual human tasks better than nearly any human.

They think it’s a straight shot from there to super-intelligence—an AI that is so much more intelligent than humans that we can’t even fathom how it thinks. A God. The arguments to claim we’re about to make gods are:

- AI expertise is growing inexorably. Threshold after threshold, discipline after discipline, it masters it, and then beats humans at it.

- We’re now tackling the PhD level.

- In the current trajectory, we should reach AI Researcher levels soon.

- Once we do, we can automate AI research and turbo-boost it.

- If we do that, super-intelligence should be around the corner.