One of the great causes of suffering is this maddening worry about what others think of us. I can go into its causes by pointing to evolutionary psychology and our hunter-gatherer roots, but that’s neither novel nor interesting. Rather, I want to delve into the asymmetry between what we know about ourselves, and the uncertainty surrounding what others know of us. Because at its core, the worry about what others think is ultimately a function of uncertainty.

Whenever we interact with someone – whether in-person or online – a gap emerges between who you are, and who you are presenting. This is why the person you are with your boss isn’t the same as the person on the couch watching Netflix. Or why the person you are with your best friend isn’t the same as the person you are with an acquaintance. Each relationship contains a culture of behavior that you oscillate between, which means that you’re constantly presenting a different version of yourself across a wide range of interactions.

What this means is that it becomes increasingly difficult to know who you really are. If a certain version of you emerges with this individual, but in the very next moment you toggle another set of behaviors with another, then that means your very identity is switching upon context. And the more you have to maneuver between various projections of yourself, the more difficult it becomes to get a handle on what “yourself” means in the first place.

This is why you’re likely exhausted after large social gatherings, and yearn to turn on the TV and watch something brainless until you drift off to sleep. The fatigue is not caused by the rigor in which your mouth is moving to talk, but rather by the constant switching of identity that occurs in these situations. When you’re worried about what someone thinks of you, it’s rarely about that person’s opinions of you. It’s about your own opinions of yourself.

_________________________

Is A.I. taking jobs from young college graduates? It depends on the job.

Stanford economists studied payroll data from the private company ADP, which covers millions of workers, through mid-2025. They found that young workers aged 22–25 in “highly AI-exposed” jobs, such as software developers and customer service agents, experienced a significant decline in employment since the advent of ChatGPT:

On the other end of the spectrum, they found for entry level workers in fields like home health aides, there is faster employment growth. That suggests this isn’t an economy-wide trend. The decline in employment really seems to be more concentrated in jobs that are more AI-exposed.

_______________________

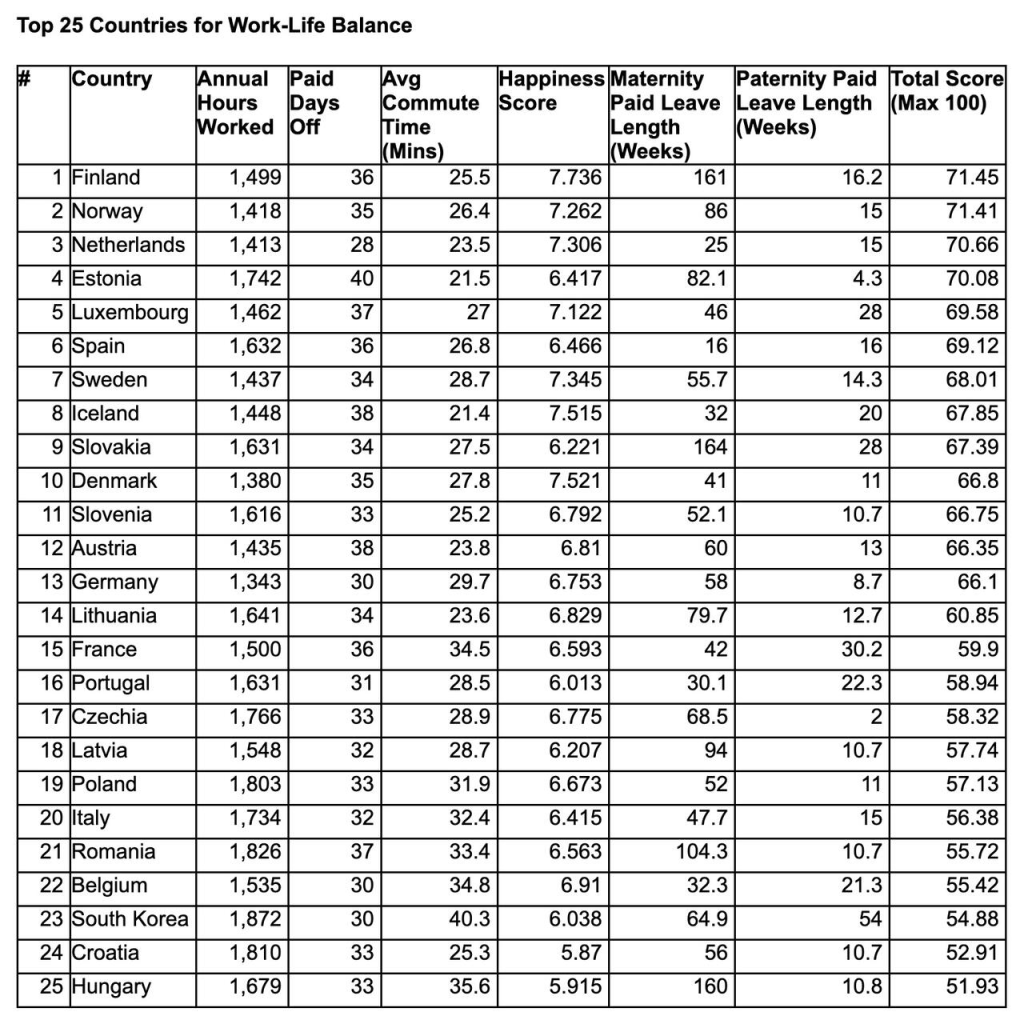

A new analysis of 39 nations reveals where employees enjoy the healthiest mix of work and personal life and on the other end of the spectrum – where long hours, limited leave, and lack of support take the greatest toll. The study assessed 10 factors including working hours, paid leave, commute length, parental support, remote work availability, and happiness scores.

Unsurprisingly, the United States finished dead last, ranked 39th out of 39. The US suffers from some of the longest working hours in the study, averaging 1,799 annually. It is the only country in the ranking without federally mandated paid annual leave or paid parental leave, and Americans devote only 14.6 hours per day to personal care and leisure.

___________________________

Interesting point on why college students are putting less effort into class: courses don’t prepare them for real jobs (like they should), so they have to spend more and more time making up the difference after class:

“A student said that coursework doesn’t prepare students to answer interview questions for finance and consulting jobs. The only way to get ready is through extracurriculars or on one’s own time. By sophomore year, his friends were fully absorbed in the internship-recruiting process. They took the easiest classes they could find and did the bare-minimum coursework to reserve time to prepare for technical interviews.“

___________________________

From Kevin Kelly on how the relationship between book publishers and authors has changed:

“Traditional book publishers have lost their audience, which was bookstores, not readers. It’s very strange but New York book publishers do not have a database with the names and contacts of the people who buy their books. Instead, they sell to bookstores, which are disappearing. They have no direct contact with their readers; they don’t “own” their customers.

So when an author today pitches a book to an established publisher, the second question from the publishers after “what is the book about” is “do you have an audience?” Because they don’t have an audience. They need the author and creators to bring their own audiences. So, the number of followers an author has, and how engaged they are, becomes central to whether the publisher will be interested in your project.

Many of the key decisions in publishing today come down to whether you own your audience or not.”

_______________________________

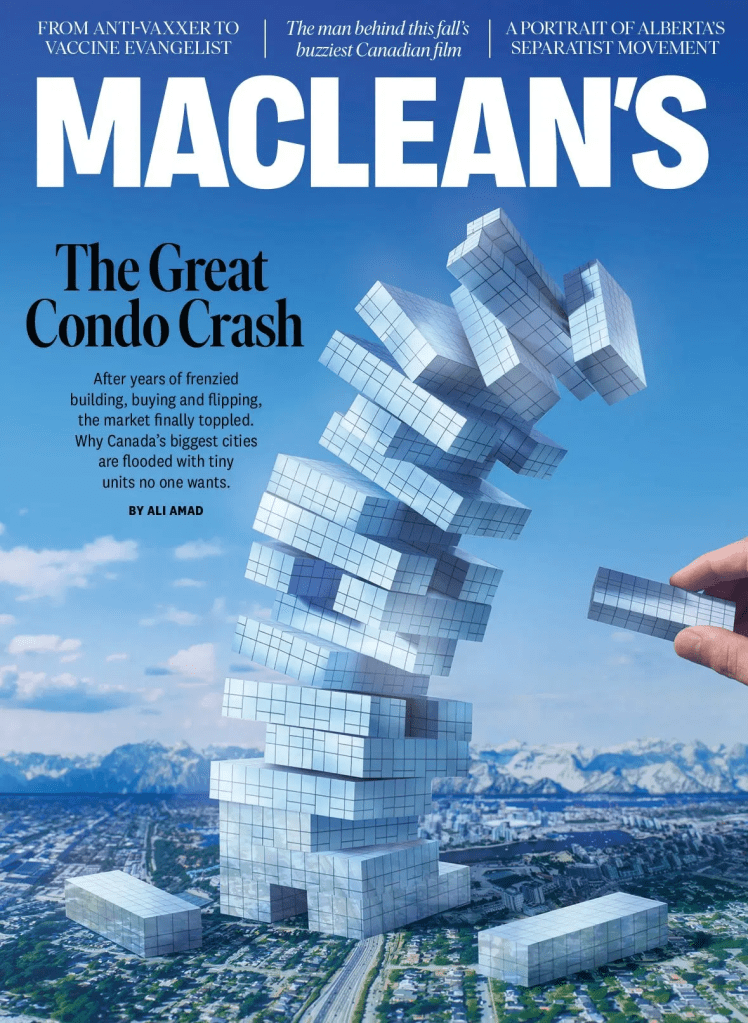

In the first quarter of 2019, the average Toronto condo cost $560,000. By the first quarter of 2022, they had soared to $808,000. Since that peak, the market has been in a painful reset.

By the first quarter of 2024, average condo values in the city had dropped by over $100,000 to $696,000, and they have continued to fall. As of this spring, the inventory of unsold units in Toronto totaled more than 23,000, which would take nearly five years to sell at the current rate. Of those, nearly 2,000 are built and sitting empty, more than 11,000 are under construction and roughly 11,000 more are in pre-construction projects.

_____________________________

As of July, there has been no reduction in import prices since Liberation Day, which are measured pre-tariff. Thus, foreign exporters in aggregate are not absorbing the tariff costs by reducing prices. This means most or all of the tariffs are being paid by American consumers and American businesses. For context, it takes about a 13% reduction in prices to offset a 15% tariff, or a 16% reduction in prices to offset a 20% tariff.

This shows up in a combination of higher consumer goods prices and/or compressed business margins of goods-heavy businesses, depending on how quickly businesses are able to pass those prices on to consumers (which will vary by industry and company; those with in-demand products can eventually pass on price increases, and those with thin margins have to eventually pass on price increases).

Consumers on the higher end of the income spectrum are less likely to change their consumption behavior and thus will basically just pay the tariffs, giving the government more revenue. Consumers on the lower end of the income spectrum are more likely to have to curtail consumption because their disposable income is scarce.

_____________________________

_______________________________

This chart shows the change in active housing inventory by state for 2025 compared to the average of 2018/2019. Orange colors mean higher inventory levels and prices are susceptible to fall, while green colors mean very low inventory and likely still price increases.