New research shows that it is specific and salient memories that influence our investment decisions rather than the collective memories (aka ‘experience’) we have. It matters for our investment decisions (in the stock market for example) if we have a memory of a good or bad experience investing in stocks. But it also matters if this memory is of a personal experience or a more distant, impersonal memory. If we have personal experiences, it makes us ‘immune’ or rather less receptive to expert advice. We think we know best because we have first-hand experience with the situation.

_____________________________

The internet commoditized information, and the widespread availability of information has devalued it because you can now find some data point, anecdote, or statistic to support any possible viewpoint, creating an environment ripe for echo chambers and false signals, which we saw this election cycle. To cut through those false signals, you have to be careful in deciding which information to look for. You have to ask good questions.

The (Presidential election) polls made the mistake of asking the folks they were surveying who they were voting for, not accounting for inaccurate responses. As a result, they got faulty information. Théo’s method, asking who “your neighbors” are voting for, proved to be more accurate, as it reduced the risk that someone would change their answer to save face (they didn’t want to say they were voting for Trump, even though they were).

If you’re trying to decide if you’re bullish or bearish on a stock, you’ll find a million arguments supporting both stances. If you have a headache, you are only three WebMD searches away from convincing yourself that you’re having an aneurysm. The antidote to this abundance of information is distillation: figuring out which information is important and discarding the rest. But distillation is downstream of interrogation: if you ask the right questions, the information filters itself.

_______________________________

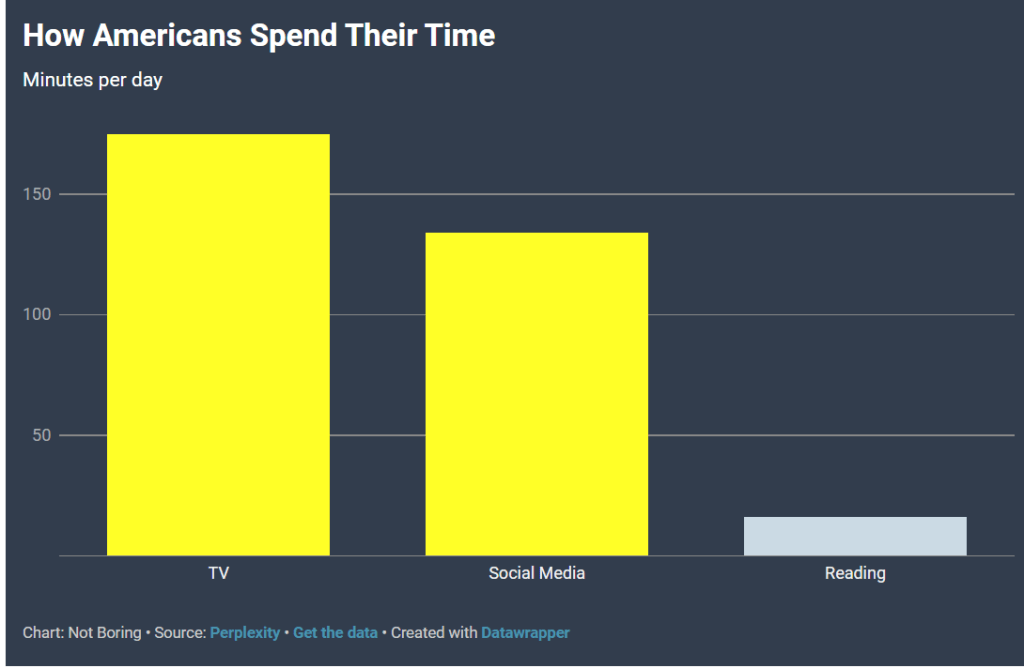

The average American spends 16 minutes per day reading. Only 46% of Americans read a book in the past year, and only 18% have read ten or more. Meanwhile, we spend nearly three hours watching TV and two hours and fourteen minutes on social media (often while watching TV). The way serious people learn is by reading. The way they share important information is by writing it down. Read, read, read. Rich people read a lot — Forbes asked a while ago, and the modal answer was two hours per day. The science backs this up: reading improves your ability to focus, slows memory deterioration and enhances memory, boosts verbal skills, and improves your ability to connect different pieces of information and ideas.

__________________________________

The cost of college is quietly going down. In-state tuition for a public university is down to $11,610 a year, compared to $12,140 a decade ago. After grant aid is applied, the average student would pay $2,480, a decrease from the 2014-2015 school year, when that amount totaled $4,140. For private schools, the net price is $16,510 a year, down from $19,330 back in 2006. Even sticker prices, the cost that is displayed by schools before any aid if applied, have mostly gone down in the last decade. The report said sticker prices in the last decade rose only 4 percent at private, nonprofit schools, decreased 4 percent at public four-year colleges and went down 9 percent at public two-year ones. The report also showed that student debt overall is down. Those graduating in debt with bachelor’s degrees are down 10 percent, or $5,600, from a decade ago, with the average debt among borrowers now at $27,100.

_______________________________

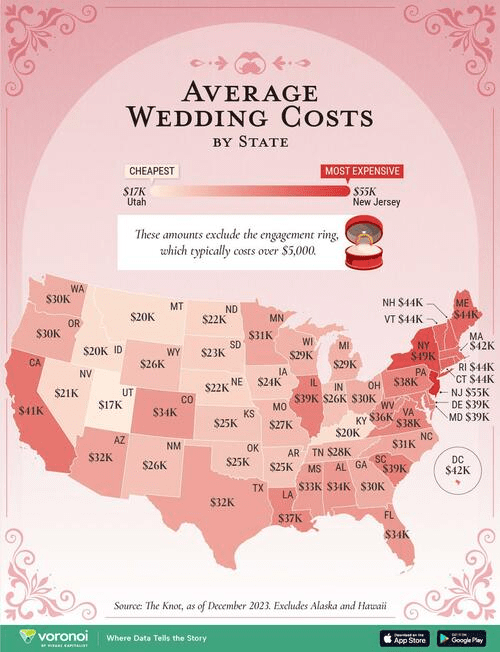

The terrifying average cost of weddings, by state, for any of the fathers of daughters out there:

__________________________

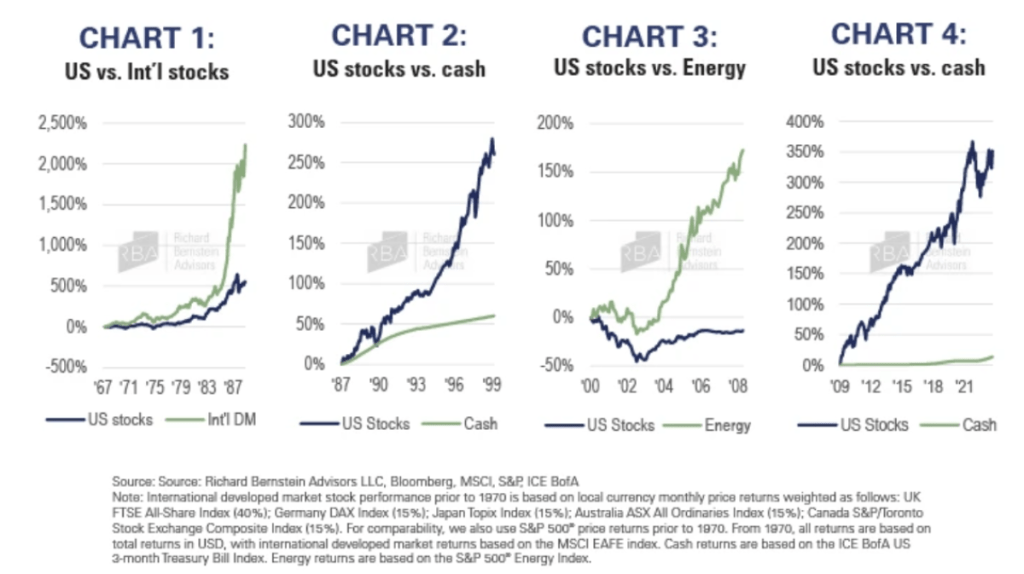

What does a once-in-a-generation investment opportunity look like? It’s when the dominant investment them of the last 10 to 15 years peaks and new leadership begins to emerge from a new asset class.

_____________________________

How risky stocks are to a given investor depends upon which part of the life cycle he or she is in. For a younger investor, stocks aren’t as risky as they seem. For the middle-aged, they’re pretty risky. And for a retired person, they can be nuclear-level toxic. The reason why stocks aren’t very risky for a young person is that you have a lot of “human capital” (the ability to make money working) left. On the eve of retirement, you don’t have any of that. Stop playing when you’ve won the game.